By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Que(e)ries: Why Do We Need To Watch The Second Coming of the HIV/AIDS Documentary?

For quite some time I’ve wanted to start a regular queer-themed column on Indiewire. The precursor to this idea — at least in large part — was written at last year’s Sundance Film Festival. It was basically a personal essay reflecting on David Weissman’s intensely affective documentary “We Were Here” (which had premiered at the festival) in relation to my own experiences with HIV/AIDS and the media.

As that essay detailed, I come from a generation of queer men that largely found out about HIV/AIDS through the mainstream media. As a result, I had by my late teens developed a problematic, unnecessary fear of the virus (and a drastic lack of real knowledge regarding it) perpetuated by these largely ignorant media representations. But then I found my way to Gregg Araki’s “The Living End,” Peter Friedman and Tom Joslin’s “Silverlake Life: The View From Here,” Derek Jarman’s “Blue,” Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman’s “Common Threads: Stories From The Quilt,” and John Greyson’s “Zero Patience,” among other examples. And collectively they liberated me. And this idea — the power of film, television and other forms of media working outside the mainstream (or occasionally and impressively within it) to produce honest and intelligent works of representation — will clearly be a dominant focus as this column hopefully continues.

READ MORE: I Wasn’t There: Sundance Doc “We Were Here” and the Importance of HIV/AIDS in Film

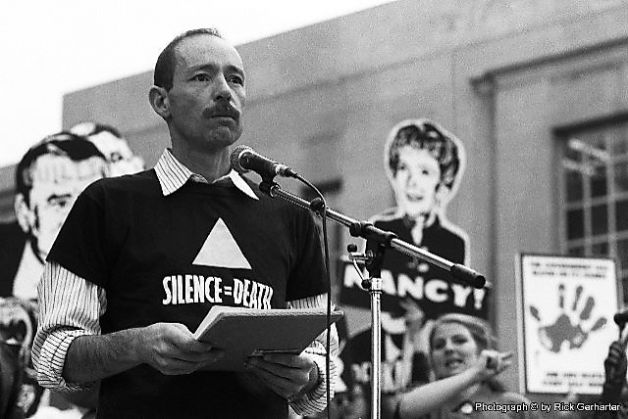

It also seemed that returning to this idea with respect to HIV/AIDS would make for an appropriate way to start things off. For one, tomorrow is World AIDS Day, a time for us all — queer, straight, female, male, HIV-positive, HIV-negative — to reflect on where our society and ourselves stand regarding HIV/AIDS. But more over, we are coming off of a year that gave us a remarkable trio of documentaries about the virus and its history: Jeffrey Schwarz’s “Vito,” David France’s “How To Survive a Plague” and Jim Hubbard’s “United in Anger: A History of ACT UP.” Joined by the aforementioned “We Were Here,” these films offer a beautiful quartet of takes on the subject that comes after a considerable absence of significant domestic HIV/AIDS representations in documentary.

Many of the films I noted earlier — “Silverlake Life,” “Blue,” “Common Threads” — were documentaries made in the late 1980s and early 1990s, a horrifyingly different context compared to today when it came to creating media about AIDS. This was filmmaking from the eye of the storm, often made by filmmakers who were unsure if they’d live to see the film’s competition (Derek Jarman’s died of AIDS-related complications just four months after completing “Blue”). People with HIV/AIDS were still battling a vicious, murderously ignorant government that was failing them when it came to — among other things — access to drugs that could save their lives. And while HIV/AIDS is by absolutely no means a problem solved, things did become a lot less immediately dire in the mid-1990s when effective drugs finally did become available and life expectancies of HIV-positive people were extended exponentially.

But around that time, the filmmaking also kind of stopped. Documentary or narrative, few worthy films dealing with HIV or AIDS domestically — either from a historic or contemporary perspective — were produced in the late 1990s or the first decade of this century. The primary exception was actually an adaptation of a stage production from the early 1990s, so it’s questionable whether it counts as a new example of representation. Either way, Mike Nichols’ astonishing 2003 HBO miniseries “Angels in America,” which adapted Tony Kushner’s Pulitizer Prize winning play (what, did you think I was talking about the film version of “Rent”?), stands as a much different example of HIV/AIDS representation than all the other films noted here. It was something of an anomaly, really, in the fact that it was produced within the mainstream media (although HBO is something of an anomaly in itself) and remained a wholly respectable portrayal of the virus and its history. But that’s a whole other qu(e)ery.

What I’ve gathered from discussing the recent quartet of documentaries with their filmmakers and subjects is that emotional exhaustion played a large role as to why artists working from more direct experiences to the epidemic than, say, Mike Nichols, minimized their output in the decade and a half followed the aforementioned advances in HIV treatments.

“So many people in my generation who have lived through the epidemic have pushed it down because multiple loss is very hard to deal with,” Daniel Goldstein, a subject in “We Were Here” who has been living with HIV for over 25 years, said after the film’s Sundance premiere. “And I think this movie has allowed me to start letting some of that in and heal from it. It’s very hard. But I’m really feeling it will be so healing for people of my generation, and hopefully it will be a revelation for young people and teach them about their history and why the world is the way it is.”

“The gay community kind of pushed away and didn’t want to revisit that era either,” Peter Staley — an activist depicted in “How To Survive a Plague” — explained in an interview. “Even AIDS activists that continued working on this rarely went back there emotionally. There was a layer of pain involved that made everybody avoid it. And I think that’s one of the primary reasons there hasn’t been any retrospective look back on that period. But now’s the time.”

READ MORE: How To Make a Powerful AIDS Doc: Talking to the Team Behind ‘How To Survive a Plague’

All four documentaries indeed take a retrospective look back at HIV/AIDS. And I’ve definitely been met with a recurring question by (questionable) people on the film festival circuit where occasionally two, three or four of the films are all playing in the same program: “Why do we need so many historical AIDS documentaries?” Obviously those people had yet to experience one or more of “Vito,” “We Were Here,” “How To Survive a Plague” or “United in Anger,” because their content makes clear the expansive narrative that was the onset on HIV/AIDS in America. A historic event on the same scale as epic war or genocides, there’s enough stories in the American narrative alone to fill hundreds of documentaries (and a few more hundred from the stories of HIV/AIDS histories around the world).

More over, each of the four films take on the subject in different ways and in different contexts.

More over, each of the four films take on the subject in different ways and in different contexts.

“We Were Here” is largely and intimately told through interviews with five people — four gay men and a heterosexual woman who was a nurse in an AIDS ward — who lived through the epidemic’s San Francisco origins. “Vito,” meanwhile, is actually not exclusively about HIV/AIDS. It’s about the life of Vito Russo, a New York-based film historian and author (he wrote “The Celluloid Closet,” among other things) who became a prominent AIDS activist when he was diagnosed in 1985. “How To Survive a Plague” and “United In Anger” have the most in common, at least on the surface. Both depict the legacy of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), a New York-based activist group that played a staggering role in getting the United States government and its agencies to finally recognize HIV/AIDS and get people the drugs they needed. But the two films are very different in the way they choose to depict this vast history, utilizing different voices and different archival footage. If you think you’ve seen both because you’ve seen one, you’re mistaken.

What unites all of these films (besides anger) is how they depict the power of people to change the course of history. The power of people working together. And this is not exclusive to queer men. While the majority of the people depicted in all four films are indeed queer, white men (who were in simple truth the majority of AIDS activists), they also make sure to note the important role women — both queer and straight — played in the epidemic (particularly the two ACT UP films). And how a small silver lining to the AIDS epidemic was how the resulting activism really brought people of different classes, sexualities, genders and races together to fight for their lives together.

All four films are inspiring each in their own way, and I’ve now each seen twice, every time in the context of public screenings where the filmmaker (and occasionally also the subjects) were present. And the Q&As that followed have paralleled the power of the film. They brought together two distinct demographics: Those that were there, and those that weren’t. People who saw their own stories (often literally) on the screen alongside people who (often for the first time) saw the history of a collective moment that in many cases made their lives possible today. And they are eager to find out what they can do to follow in the footsteps they saw on screen.

“I think that’s why I made this film,” Jim Hubbard said at a screening on “United in Anger” at Concordia University in Montreal last week, when a young audience member basically asked how to go about contributing to activism today. “So that there is a blueprint. I don’t think this is the only way to go about it. And I think people have to reinvent [activism] everytime. If people in ACT UP hadn’t seen the footage of civil rights protestors… That knowledge would have been much harder to convey.”

Hopefully these films inspire young people to take on an issue which remains extraordinarily problematic (Hubbard also suggests heading to ACT UP’s website, which is an invaluable resource). Every month, 1,000 Americans under the age of 24 become infected with HIV, which absolutely remains an incurable infection (and one that costs $400,000 to treat over a lifetime). And while HIV/AIDS is surely not a disease exclusive to men who have sex with men (it never was), this demographic remains staggeringly disproportional in terms of new infections. In 2010, 72 percent of the estimated 12,000 new HIV infections in young people occurred in men who have sex with men. This despite the suggestion that we make up less than 5% of the overall population. And infection rates are just one issue of many (social stigmas, criminalizing non-disclosure, drug funding both domestically and even more critically in developing nations).

Clearly a new generation of people are not learning from the astonishing struggles the people depicted in these films had to go through. And while the optimal, unrealistic situation is that you come out of any of these films with your inner activist unleashed (or their inner filmmaker as these docs should just be the beginning of reflective media on HIV/AIDS), at the very least you should find yourself simply coming out of these films. And what better way to do it then on World AIDS Day, when screenings of all four films are happening all across the country. If you’re a New Yorker, you can actually watch “Vito,” “Plague” (with France and Larry Kramer in attendance for a Q&A) and “Anger” (with Hubbard and Sarah Schulman in attendance for a Q&A) back to back at MoMA Saturday starting at 1pm (info here). If that’s not an option, check out the websites for “United in Anger,” “We Were Here,” “Vito” and “How To Survive a Plague” for screening information across the US and Canada or just spend 5 minutes with the obvious Google keywords. It’s truly the least you can do.

Peter Knegt is Indiewire’s Senior Editor. Email him for suggestions for future “Qu(e)eries” columns at peter@indiewire.com. He’d love for it to a be a collaborative effort.

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.