By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Here Are Mike Nichols’ Best Films, From ‘The Graduate’ to ‘The Birdcage’

When Mike Nichols passed away at 83 this morning, the film and theater world lost one of its greats.

Nichols leaves behind a staggering body of work, but he’s been frequently deemed an “invisible auteur”: His visual style was never really consistent, but his themes — the chasm between generations, the purgatory of home, family feuds, seduction and manipulation, dolphin espionage — and his incredible gift with actors never wavered.

If you dig deeply into Nichols’ oeuvre, one thing becomes immediately apparent: all of his films are anchored by great performances. Nichols, whose prodigious career as a stage director arguably trumps his film career (that’s no slight: both are undoubtedly great, but his stage career is unbelievable), has always possessed an uncanny ability to cajole stellar performances from his casts.

Most of his early films, particularly “The Graduate” and “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” are visually lush and stylish, but as Nichols’ career progressed, his cinematic approach became less dynamic and more patient. His career seems to settle on actors willing to open themselves up to his material. All of Nichols’ best films, and even his lesser ones — “Closer,” for instance, is by no means great, but has four great performances, especially by Clive Owen — are acting master classes.

READ MORE: Mike Nichols Dies at Age 83

To honor Nichols, we’ve put together a short list of his best films.

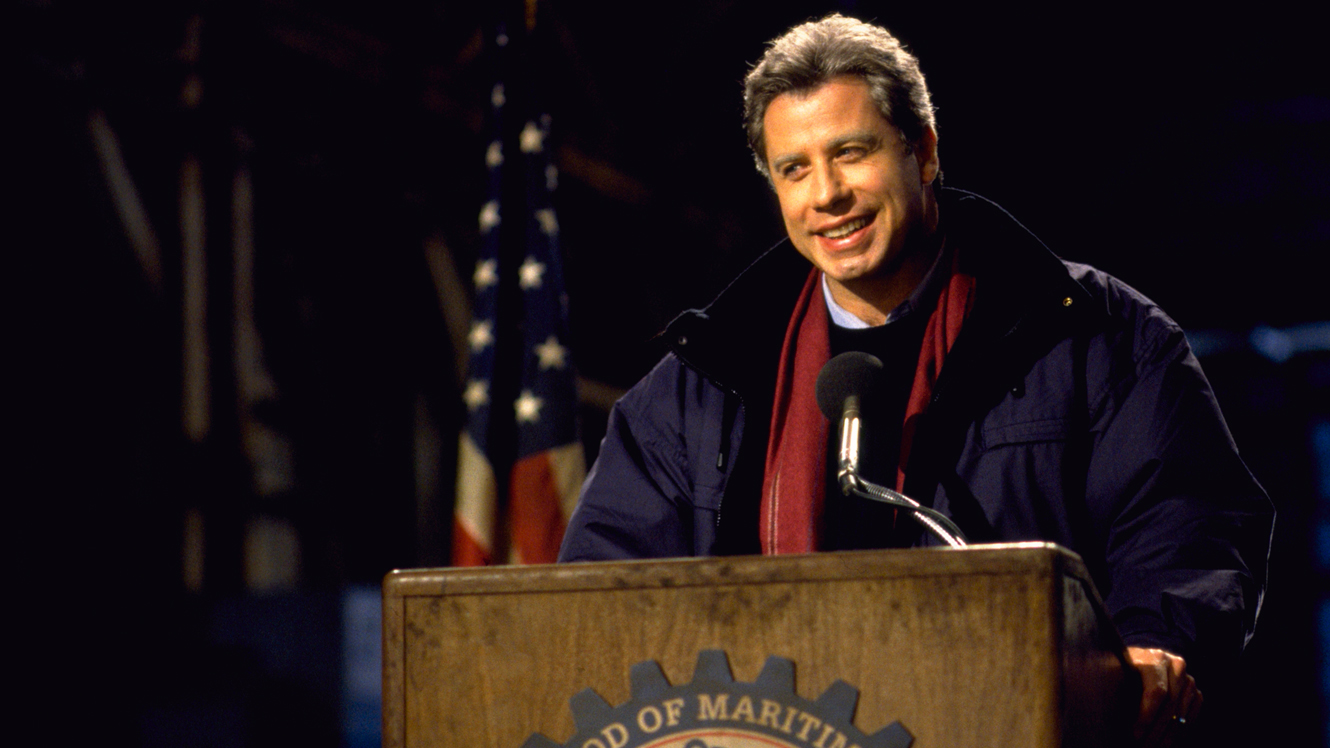

Primary Colors (1998)

John Travolta is wonderfully fun as Jack Stanton, a Bill Clinton-esque president with a seemingly constant desire for women. As Lisa Schwarzbaum said when the film first came out, Travolta’s performance is “one of those thrilling confluences in pop culture, a blurring of politics, entertainment and newspaper headlines that titillates and rewards audiences for thinking the worst about politicians and the best about movie stars.”

John Travolta is wonderfully fun as Jack Stanton, a Bill Clinton-esque president with a seemingly constant desire for women. As Lisa Schwarzbaum said when the film first came out, Travolta’s performance is “one of those thrilling confluences in pop culture, a blurring of politics, entertainment and newspaper headlines that titillates and rewards audiences for thinking the worst about politicians and the best about movie stars.”

Travolta really finds the fragmented soul of Stanton, and Nichols’ typically syncopated rhythm allows Travolta breathing room; the movie is very funny, of course, but it’s those isolated moments of serenity, when Travolta plumbs the depths of Stanton’s ambiguous morals, that make “Primary Colors” better than all the other myriad post-Monica Lewinski movies.

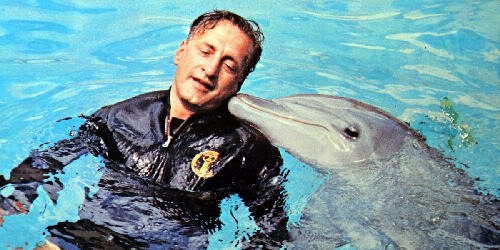

The Day of the Dolphin (1973)

This is the point when most of you say, “Um, what?” But stick with me here: “The Day of the Dolphin,” so wryly and keenly parodied on “The Simpsons” and with less wit on virtually every other satirical TV series since, is seriously misunderstood. It’s escapism, but it’s not escapist claptrap. Pauline Kael succinctly encapsulated the general feeling of resentment the film spurred when she intoned that if dolphins are the best thing Nichols can think of, maybe he should stop making movies.

This is the point when most of you say, “Um, what?” But stick with me here: “The Day of the Dolphin,” so wryly and keenly parodied on “The Simpsons” and with less wit on virtually every other satirical TV series since, is seriously misunderstood. It’s escapism, but it’s not escapist claptrap. Pauline Kael succinctly encapsulated the general feeling of resentment the film spurred when she intoned that if dolphins are the best thing Nichols can think of, maybe he should stop making movies.

But the film is a wicked gag, a comedy as dark as an oil tanker spill. It’s a movie about dolphins as spies, so you probably shouldn’t take it too seriously, and George C. Scott, that stone-faced golem of unwavering severity, hasn’t been this much fun since Kubrick manipulated him into histrionics on the set of “Dr. Strangelove.” Stylish and silly, this is the work of an artist of the highest caliber having a good time with a big budget, something we rarely see today.

Heartburn (1986)

Nichols and Nicholson reunite for a deeply, darkly, scathing look at love and its inevitable degradation, Nichols’ favorite theme. Nicholson is a political columnist (read: an asshole) and Meryl Streep is his wife, a New York City-based food writer (read: pretentious). The beloved Nora Ephron penned the screenplay, which is very obviously autobiographical and makes no attempt to veil her disdain for the husband character. But, as is the norm in Nichols’ movies, the acting trumps all.

Nichols and Nicholson reunite for a deeply, darkly, scathing look at love and its inevitable degradation, Nichols’ favorite theme. Nicholson is a political columnist (read: an asshole) and Meryl Streep is his wife, a New York City-based food writer (read: pretentious). The beloved Nora Ephron penned the screenplay, which is very obviously autobiographical and makes no attempt to veil her disdain for the husband character. But, as is the norm in Nichols’ movies, the acting trumps all.

Unfairly maligned for being too bitter and replete with unlikeable characters, “Heartburn” is an unflattering, unfiltered look at how much stress a relationship can endure before it bends and breaks. Streep is good, but Nicholson is revelatory. He’s a philandering jerk, but an enthralling philandering jerk. Watch the scene in which he discovers his kitchen doesn’t have a door. Dark-comedy magic.

The Birdcage (1996)

Nichols’ adaptation of the now-forgotten French classic “La Cage aux Folles” (it’s spectacular, go watch it) received a much-belated second life earlier this year when the tragic news of Robin Williams’ death broke. Of course it’s sad that the untimely passing of an iconic entertainer was responsible for a movie getting a critical reevaluation, but at the same time at least the film, in particular Williams’ fantastic turn, finally got their due. Williams is the owner of a drag club in South Beach and Nathan Lane (at his most flamboyant) is Williams’ long-time partner and creative muse. The main story involves Williams’ son getting married to a young woman whose parents are uber-conservative (played with wonderful restraint by Gene Hackman and the eternally undervalued Dianne Wiest), but honestly no one really cares about them. The heart and soul of the film is Williams and his relationship with Lane.

Nichols’ adaptation of the now-forgotten French classic “La Cage aux Folles” (it’s spectacular, go watch it) received a much-belated second life earlier this year when the tragic news of Robin Williams’ death broke. Of course it’s sad that the untimely passing of an iconic entertainer was responsible for a movie getting a critical reevaluation, but at the same time at least the film, in particular Williams’ fantastic turn, finally got their due. Williams is the owner of a drag club in South Beach and Nathan Lane (at his most flamboyant) is Williams’ long-time partner and creative muse. The main story involves Williams’ son getting married to a young woman whose parents are uber-conservative (played with wonderful restraint by Gene Hackman and the eternally undervalued Dianne Wiest), but honestly no one really cares about them. The heart and soul of the film is Williams and his relationship with Lane.

These aren’t gay caricatures, and Nichols has always been more willing to explore gender roles than other male filmmakers of his generation. Nichols obviously understands theater and theatrics, but his camerawork is surprisingly unstylish here, which could, in the hands of a lesser director, feel lazy or overly content. Instead, it allows Williams the space and time to really explore his character. The actor, pretending to be a straight entrepreneur for his son’s future in-laws, is in turn heartbroken and tranquil, eccentric and rapturous.

Angels in America (2003)

An HBO mini-series adapted from Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer-winning play is one of first truly great made-for-TV cinematic productions. Nichols’ preternatural ability to coax amazing performances from his cast is on full display here. Watch the scene in which James Cromwell’s doctor explains AIDS to Al Pacino: Cromwell speaks steadily and calmly, trying to repress emotion (he frequently stares down at his desk as he divulges more details), and Pacino continues to silently put his clothes on. His face looks weathered and weary and those cavernous eyes, wreathed with bags. When Cromwell finishes, Pacino says, “Very interesting, Mr. Wizard, but why the fuck are you telling me this?” Cromwell responds, “Well, I have bad news.” Pacino doesn’t take so kindly to what he thinks is an insinuation that he’s a homosexual (he does have sex with men), and his subsequent monologue is simultaneously searing and tragic. Meryl Streep, Patrick Wilson, Mary-Louise Parker, and Jeffrey Wright are all spectacular. But Pacino is utterly vicious in his denial; that he and Nichols make us care for his bitter lawyer at all is a marvel.

An HBO mini-series adapted from Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer-winning play is one of first truly great made-for-TV cinematic productions. Nichols’ preternatural ability to coax amazing performances from his cast is on full display here. Watch the scene in which James Cromwell’s doctor explains AIDS to Al Pacino: Cromwell speaks steadily and calmly, trying to repress emotion (he frequently stares down at his desk as he divulges more details), and Pacino continues to silently put his clothes on. His face looks weathered and weary and those cavernous eyes, wreathed with bags. When Cromwell finishes, Pacino says, “Very interesting, Mr. Wizard, but why the fuck are you telling me this?” Cromwell responds, “Well, I have bad news.” Pacino doesn’t take so kindly to what he thinks is an insinuation that he’s a homosexual (he does have sex with men), and his subsequent monologue is simultaneously searing and tragic. Meryl Streep, Patrick Wilson, Mary-Louise Parker, and Jeffrey Wright are all spectacular. But Pacino is utterly vicious in his denial; that he and Nichols make us care for his bitter lawyer at all is a marvel.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966)

Nichols debut feature film was aptly described by Stanley Kauffman as a “Houdini feat.” With an astounding cast (Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Sandy Dennis, and George Segal), Nichols uses a wide, cinematic scope to capture all four of his main players in single shots, at once retaining the feeling of the play without disrupting the actors’ rhythm by cutting from shot to shot. Taylor nabbed a best actress Oscar, and Dennis won Best Supporting Actress, though everyone is great. Like Kurosawa or Robert Rossen circa “The Hustler,” Nichols keeps the camera close, indecently prying into the lives of his characters, and all of the actors are ready to show their ugly sides.

Nichols debut feature film was aptly described by Stanley Kauffman as a “Houdini feat.” With an astounding cast (Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Sandy Dennis, and George Segal), Nichols uses a wide, cinematic scope to capture all four of his main players in single shots, at once retaining the feeling of the play without disrupting the actors’ rhythm by cutting from shot to shot. Taylor nabbed a best actress Oscar, and Dennis won Best Supporting Actress, though everyone is great. Like Kurosawa or Robert Rossen circa “The Hustler,” Nichols keeps the camera close, indecently prying into the lives of his characters, and all of the actors are ready to show their ugly sides.

The Graduate (1967)

All you need to know about “The Graduate” to understand why it’s so great is that final pair of shots. Dustin Hoffman and Katharine Ross sit victoriously on the back of a bus, as Ross’ family recedes into the background. Ross is still in her wedding dress, her former husband-to-be now just a blur behind her. Facing straight ahead, both Hoffman and Ross look jocular, having successfully run away together like all star-crossed lovers aspire to. But very quickly their jovial visages begin to sink, and worry seems to seep into their eyes. Hoffman’s mouth begins to slump, as if it’s suddenly gained ten pounds. Cut to an exterior shot of the bus driving away, and we see Hoffman and Ross through the window, but they’re separated: it’s two windows, not one. (Where do you even find a bus like that?)

All you need to know about “The Graduate” to understand why it’s so great is that final pair of shots. Dustin Hoffman and Katharine Ross sit victoriously on the back of a bus, as Ross’ family recedes into the background. Ross is still in her wedding dress, her former husband-to-be now just a blur behind her. Facing straight ahead, both Hoffman and Ross look jocular, having successfully run away together like all star-crossed lovers aspire to. But very quickly their jovial visages begin to sink, and worry seems to seep into their eyes. Hoffman’s mouth begins to slump, as if it’s suddenly gained ten pounds. Cut to an exterior shot of the bus driving away, and we see Hoffman and Ross through the window, but they’re separated: it’s two windows, not one. (Where do you even find a bus like that?)

It’s as sad an ending as Hollywood has ever produced, and widely misunderstood. Add in the iconic Simon and Garfunkel score, the sultry manipulation of Mrs, Robinson, the fact that Mr. Feeney from “Boy Meets World” is Hoffman’s dad, the shimmering cinematography and playful editing, and you have one of the all-time great American comedies.

Carnal Knowledge (1973)

Nichols’ most acerbic film depicts the sexual exploits of a pair of life-long friends (Jack Nicholson and Art Garfunkel, in his first of several sexually intense performances). It’s a relentlessly tough (but never mean-spirited) examination of misogyny and ubiquitous objectification. At times it seems as though the entire world of “Carnal Knowledge” is rife with sexually-needy but vacuous meat sacks. These men are incapable of knowing, touching, understanding, or loving women. They don’t overtly hate women — theirs is more in the vein of that casual, embedded sexism that people love to deny and ignore.

Nichols’ most acerbic film depicts the sexual exploits of a pair of life-long friends (Jack Nicholson and Art Garfunkel, in his first of several sexually intense performances). It’s a relentlessly tough (but never mean-spirited) examination of misogyny and ubiquitous objectification. At times it seems as though the entire world of “Carnal Knowledge” is rife with sexually-needy but vacuous meat sacks. These men are incapable of knowing, touching, understanding, or loving women. They don’t overtly hate women — theirs is more in the vein of that casual, embedded sexism that people love to deny and ignore.

Nichols’ fourth feature is extremely economical and never places blame or points a finger. He doesn’t try to make Nicholson and Garfunkel into “bad guys,” but displays more interest in showing how their way of thinking — this imbued notion of young men desperately and justifiably seeking sexual gratification — is nebulous and unsettling.

Both men want to be dominated by women, but don’t want to let women dominate them. Nicholson, in one of his very best performances, finds the empathy in what could have been a scumbag caricature. But “Carnal Knowledge” is earnest, sincere and open-minded. And it’s wicked funny, to boot — exactly the sort of unlikely combo Nichols pulled off better than anyone.

READ MORE: Remember Mike Nichols By Streaming His Films Online

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.