By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Gus Van Sant: On Working with William S. Burroughs and the Evolution of Indie Film

Paula Bernstein

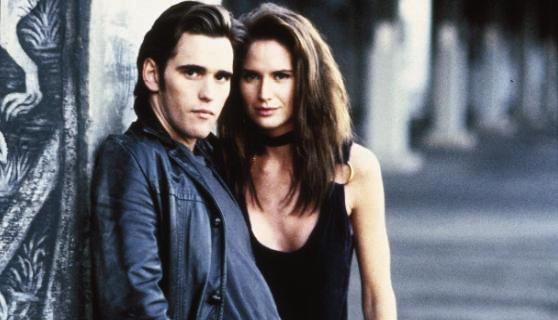

It was a homecoming of sorts for Gus Van Sant on April 30 when the director participated in a conversation following a special 35mm screening of “Drugstore Cowboy” at the Northwest Film Center in his hometown of Portland, Oregon. The 1989 film, which stars Matt Dillon and Kelly Lynch as junkie outlaws who rob drugstores, was partially shot in the area surrounding the Film Center.

The screening was part of the Northwest Film Center’s “Essential Gus Van Sant (& His Influences),”a series of Van Sant movies as well as others that influenced his work including films by Stanley Kubrick, Werner Herzog, and Béla Tarr.

Mario Falsetto, Professor Emeritus in Film Studies at Concordia University, Montreal, and author of the just-published Conversations with Gus Van Sant,” asked the Academy Award-nominated director a few questions about “Drugstore Cowboy” before Van Sant fielded questions from the audience. Here’s the key takeaways from the event, in Van Sant’s own words.

“Drugstore Cowboy” was based on a true story.

“Drugstore Cowboy” was based on a true story.

[It was based on the semi-autobiographical novel by] James Fogle, who grew up in Tacoma, [Washington] and this is a depiction of his friends and his drug crew and his road crew. He had spent most of his time in prison growing up. The first time he went in he was 15 years old. He had many, many stories about escaping. One time he escaped in the ’50s at just the wrong moment, when they were testing the Atomic Bomb and as they’re running across the desert, the sky lit up and they could spot him… weird stories like that, but they were always very funny.

He had written a few different novels. This was one of them. There were at least four of five, about his time inside San Quentin [State Prison]. While we were making this (“Drugstore Cowboy”), he was in Walla Walla State Penitentiary and he had sort of gone in and out of jail even after we made this film.

This film got him back out because it was well-known enough that I think the prison system in Washington State looked well upon him and let him out. Then he got in trouble again and went back in. He’s gone now. He died a few years ago. This [material] was written in the ’60s and it always had a very pulp-fiction feeling, which was something that he lived and also was a fan of – and it was brought to life by a class that he was taking in his prison. The teacher of the class, who had written “The Bird Man of Alcatraz,” was hooking up students that he had outside of the prison system with inmates in the prison system to help them get their books published.

“Drugstore Cowboy” was Van Sant’s first Hollywood production, a big shift from the low-budget “Mala Noche.”

“Drugstore Cowboy” was Van Sant’s first Hollywood production, a big shift from the low-budget “Mala Noche.”

“Mala Noche” was done with a very small budget and a very small crew… we were able to shoot very fast. In getting this (“Drugstore Cowboy”) going, the independent film scene was becoming bigger and bigger. It was a budgetary style to make a film that was kind of mimicking Hollywood where the budgets were much bigger. This was shot by Bob Yeoman, who does Wes Anderson’s movies. He had a pretty good size grip crew and lighting crew. It was quite different. It was a lot of trucks and a lot of personnel, very different than what I experienced on “Mala Noche.”

I was trying to be true to a vision I had, which was altered because of the slowness of the crew and of my ability to push the crew. If I had a different temperament, I might have been able to scream at them louder and get them to move. But it was pretty slow.

READ MORE: Wes Anderson’s DP Robert Yeoman on Bringing ‘The Grand Budapest Hotel’ to Life

William S. Burroughs and his assistant wrote his own lines for “Drugstore Cowboy.”

William S. Burroughs and his assistant wrote his own lines for “Drugstore Cowboy.”

Before I made “Mala Noche,” I had made a short film called “The Disciple of D.E.,” which was from a short story that William Burroughs had written around 1974. Somewhere along the line, I asked him permission to make this short film. I was in touch with him and his assistant in 1975 and much later when we were making this film in 1987 and 1988, there was a character whose name was Old Tom and he lived in an assisted living home and he was an aging junkie who was somebody who was somewhat slipping off his program and Bob [played by Matt Dillon in the film] ends up in the same hotel and recognizes Old Tom as an older generation of the same ilk that he was, an older junkie, an older con man, and that’s the way James Fogle had it in the script.

I sent [the script] to Burroughs to see if he wanted to be in the film. He liked it quite a bit, but he didn’t like the kind of down-and-out-had-nothing-going-on quality of this aging character. He thought he could have something going. He also turned him into a priest, which was a character he had written about, various priests in his books. So they started with that. I think James, Burroughs’ assistant, did most of the writing, emulating Burroughs’ writing.

Everything that Burroughs says is pretty much not anything that Fogle wrote. It’s pretty much what James Grauerholz wrote with William Burroughs and it’s emulating his philosophy. He also insisted on, when he came here (to Portland) to shoot, he insisted on shooting everything in one day, which we accomplished. Some of those shots were done in the park right here [by the Northwest Film Center at the Portland Museum of Art]. It was pretty much done right around this building.

Matt Dillon was not Van Sant’s first choice to play Bob in “Drugstore Cowboy.”

Matt Dillon was not Van Sant’s first choice to play Bob in “Drugstore Cowboy.”

When I was first trying to get things going, I somehow got in touch with Tom Waits. Tom Waits was more the type of guy who resembled the character. Matt [Dillon] was a younger version. Tom could gripe about “the younger kids today,” whereas Matt was still a kid. So Tom Waits wanted to do it. I had given him a script. Then when I went to the company that was financing it and I mentioned Tom Waits, they had him in another film, that was one thing. But I think they had made “The Kiss of the Spider Woman” with William Hurt and he had won an Oscar, so they were really in the game of they could put somebody in there would would attract Oscar attention.

So they were aiming really high, like Jack Nicholson. And I think Sean Penn was in there, Matthew Modine. Those three. I don’t know what happened with Sean, but Nicholson said ‘no’ and Matthew Modine’s agent said ‘no.’ Then somewhere along the line, Matt Dillon was suggested by agents. It sort of became agents arguing about it and not even myself. Tom was just in a different movie in the same company, which was kind of sad. As a young filmmaker, I was playing this game of “whatever you guys say,” which is not very comforting.

John Waters and John Sayles inspired him to make films.

I was an art student in the early ’70s in Rhode Island and the first film that I saw – there were other ones I wasn’t aware of, like “Little Shop or Horrors,” which was the Roger Corman film, but I realized there was such a thing as a film made with a really small budget. The first one I kind of related to was “Pink Flamingos” by John Waters, which was made for about $10,000 and it took years to make it with his friends. I thought, “Wow, you can actually make a work with pretty much not very much money and have people chip in.” That was ’72 and by the time I made “Mala Noche” it was ’82 or ’83 or ’84. It was kind of following in that vein.  The evolution of indie film

The evolution of indie film

John Waters was one indication and then John Sayles was more upgraded, a little more commercial, a little less extreme than John Waters and [Sayles’] “Return of the Secaucus Seven” was this indie hit that swept the nation. It was like this is a new cinema. The ’70s fueled that also with “Easy Rider,” so that was happening simultaneously with John Waters.

But there was this thing going on in, say 1982-83, companies would actually come in and give seminars at The Northwest Film Center. They would talk about their business and they were looking for young filmmakers to make films that they could distribute. At the same time, art houses were pushing not just old revival films, but new things that were being made. That came to a pinnacle in maybe 1990 and kept going. It finally became absorbed by the industry itself. They saw that these companies could make a certain amount of money. With hits like “Pulp Fiction,” they started to buy the companies, which a lot of them did. Once they bought them, they became disillusioned and shut them down and there’s new companies now that have emerged.

I think that the things you need to make movies, you can really do it on your phone and with even smaller amounts of money than John Waters. It’s just a whole new game. It’s a little bit daunting for me because of the internet and things that are on the internet and the way cinema works now.

Watch the trailer for “Essential Gus Van Sant (& His Influences),” which runs from April 23-June 5, below:

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.