By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

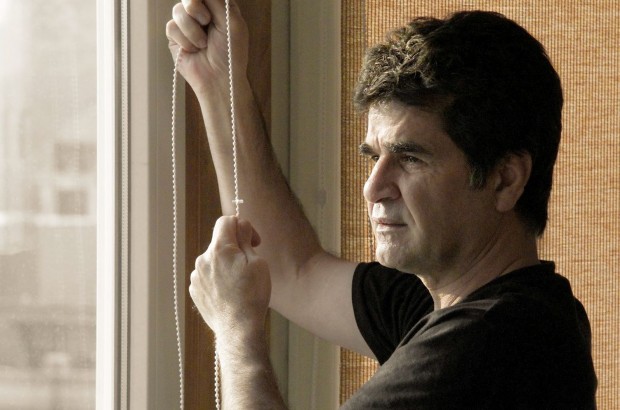

‘Closed Curtain’ Director Jafar Panahi Talks About Making Movies Under House Arrest: ‘Put Yourself in My Shoes’

Eric Kohn

If you’ve been following Jafar Panahi’s story from afar, it’s almost chilling to hear his voice on the phone. In 2010, the acclaimed Iranian filmmaker (whose credits include “The White Balloon” and “The Mirror”) was detained by the government and spent time in jail before being placed under house arrest. Eventually, he was prohibited from leaving the country and banned from making movies for 20 years. Around that time, he managed to make a creative diary of his experience awaiting trial with the wry title “This Is Not a Film,” which was famously smuggled into the Cannes Film Festival on a flash driver hidden in a pastry. Mourning the restrictions on his creativity, in “This Is Not a Film” Panahi turned his desperation into a narrative device, resulting in his most innovative achievement irrespective of its bleak context.

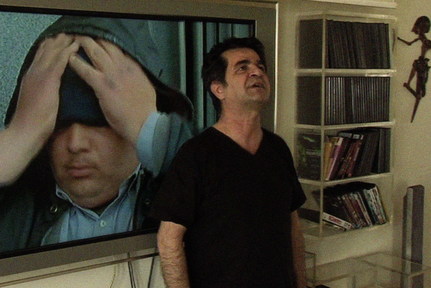

But it wasn’t his last: Next week, Variance Films will release “Closed Curtain,” which renders the literal frustrations of “This Is Not a Film” in abstract terms. The movie begins with the story of a criminal on the lam with his trusty canine and taking refuge in a large home by the sea, where he encounters two other desperate characters. But eventually Panahi himself enters the scene, contemplating his story from afar and eventually overtaking it, quietly turning “Closed Curtain” into a poetic meditation of his commitment to filmmaking against impossible odds. Shot within the constraints of the director’s vacation home, “Closed Curtain” is informed by the limitations placed on its maker, but also a remarkable approach to defying them.

Even so, there’s an uneasy quality to watching another of Panahi’s beautiful movies, since there’s no telling how much longer he can keep it up. But the director has certainly embraced the challenge, even managing to pick up the phone for an interview with Indiewire this week. Sounding alternately weary and determined, Panahi spoke through a translator as he explained the genesis of “Closed Curtain” and why he continues to make movies in spite of the risks at hand.

“Closed Curtain” starts as one type of movie and turns into something else. What was the genesis of this idea?

Before I made this movie I wasn’t feeling well. I had a lot of ideas including one that involved a person and his dog and not knowing where he would take that dog when it was under some threat. Then I happened to go to my villa on the seacoast and when I arrived I realized that the windows had been broken. That gave me the idea that maybe this person I had in mind for a long time could end up bringing his dog here. So it was a combination of reality and imagination and even some surrealistic elements.

In some ways, the approach calls to mind your film “The Mirror,” which also deals with multiple, conflicting realities.

When we were making “The Mirror” we were dealing with a realistic world that later transferred into a world even more realistic to the point that it became like a documentary. In this film, what we’re doing is the exact opposite. We start with something like reality and it becomes more complex and surreal as we go ahead. To tell you the truth, at some point in my career, I couldn’t see myself doing a movie like this, something that delves into the imagination of an artist — but with a completely different language. It’s part of what my career has come to. It’s natural to have some part of my previous movies in this one as well.

When I saw the movie at the Berlin Film Festival, there was an audible gasp in the audience when you suddenly appeared onscreen. This is the second time you served as a character in your own story, following “This is Not a Film.” Why did you decide to take this approach?

Whatever I do in these circumstances somehow reverts back to myself because I’m working in limited spaces. Also, I’m trying not to use other people as it might cause problems for them — as it did for the two people who appeared in this film, Maryam Moqadam and Kabuzia Partovi, who also co-directed the film with me. They had their passports confiscated from them after the film’s premiere. Since I don’t want to cause other problems with other people, I have to reduce everything to myself. I think of myself as the person behind all of it. I was aware that my appearance in this movie shocked the audience, but the screenwriter you see entering the house with that dog is a reflection of my own character. It’s the kind of story I might be part of. At this point, I just have to do what I can with the constraints in front of me.

And we don’t want to get you into more trouble for it, but here you are under house arrest and banned from filmmaking yet still promoting the movie. The American trailer explicitly mentions that you violated the ban. Considering the risks that you face for violating government orders, why are you doing all this?

I just want you to put yourself in my shoes as a filmmaker who can’t do anything else but make films, and doesn’t want to do anything else. How much time do I have left? Do I have 20 years left to live? I cannot stay idle. I know this is what they want. They let me out of a small prison and released me into a much larger one. When I was in a small prison, I knew there was nothing I could do there. Every movement was being watched. I just had to wait for my jail term to end. Now that I am so-called “free,” but in reality in a larger prison, I just have to do something and cannot stay idle and let my life be wasted. They’ve slapped me with this 20 year ban, but they can just make it 30 years or 50 years and it won’t make a difference to me.

So does that mean you plan to make more movies?

Well, I hope I can make other movies, but I’m not sure. The problem is that I’m fed up with surreptitiously making everything in very confined spaces and not having the freedom to work as I used to. I don’t know how many movies of this nature I can continue to make. I don’t want to change my kind of filmmaking. Just the mere thought of my future projects has turned into some sort of mental sickness for me. It makes me feel sick thinking of all these projects I’d like to do but I don’t have the ability to make them.

I cannot just stay idle, but I don’t know what kind of work I can do to satisfy myself. Remember, a few months ago, because they didn’t allow me to go outside of the house, I said, “OK, I’ll open my windows and take shots of the sky.” I ended up with about 15 nice still photographs. But then when I went to print them, at the lab, they refused to do it. They said they had instructions from the government that I wasn’t allowed to get them printed.

I had a crazy idea a while back. In order to stay connected to society, I was thinking of driving a cab, so I could stay close to people and talk to them. But I knew I would be tempted to take a camera inside a cab, and that wouldn’t work.

Why not?

I would love to make that movie as well but the problem is I’d want to make it for real — to use the script I want to use. I don’t want to do it with a hidden camera. Because that’s the same restriction I’ve suffered with making my last movies.

You’ve received support at film festivals from around the world. How has this kind of publicity impacted your situation?

The kind of support that I got helped me and it was because of that support that they had to free me. I remember when they were threatening that they would keep me so long that I’d lose all my teeth. They would say that I was a special guest and they’d never let me go. But the international pressure forced them to let me go. Sometimes, people think the international pressure doesn’t influence [the government], that they don’t care about it. But that’s not true. When you are in prison, they try to make you cooperate with them. They promise you freedom if you cooperate. If they have to let you go, then they try to make your life outside prison so miserable that sometimes you wish you could do what they want. I worry about support from my colleagues inside the country because they may pay a price for me.

Many people outside of Iran are aware of your situation, whether or not they know your movies, and certainly want to help. What can they do?

Outside of Iran, it’s up to them if they’d like to continue to support or care about this situation. When I see all this international support, I immediately think of the other intellectuals in jail and just because they are not famous, they aren’t getting noticed. I think that’s wrong.

Several of your contemporaries, including Mohammad Rasolouf and Abbas Kiarostami, have either decided to work outside the country or wound up being forced to do so. In light of these decisions, does Iranian cinema have a future?

I’m really optimistic about the future of Iranian cinema because of all these young and talented filmmakers. Some of my colleagues are working outside of Iran. There’s nothing wrong with that. They should be free to work inside or outside. But what makes me hopeful, after making this picture, is this pool of talented young filmmakers who can use the same all-digital cameras to make their own movies. There was a time when the government had a monopoly on all the filmmaking equipment. But right now, if you’re a young filmmaker, you don’t have to go to the government to make your films. The camera and software is available to you so you can make your movie. I myself was supposed to make a movie outside of Iran and would welcome that situation, but I would want to know that I can return.

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.