By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Jersualem Film Festival Head Explains Why Palestinians Won’t Show Films at the Festival

Laya Maheshwari

By any metric, the CEO of the Jerusalem Cinematheque has had an eventful first year at her new job.

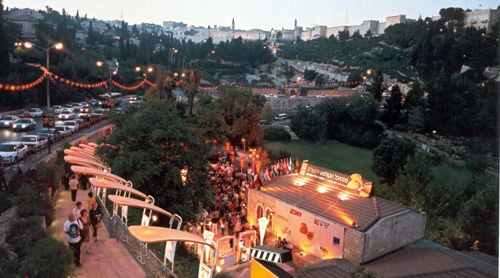

The Cinematheque was founded in 1973 by Lia van Leer, who served as director for the theatre and the festival for decades. Once she retired, the post kept changing hands, the body’s budget deficit grew to alarming levels and the employees turned angrier. During this turmoil, the Cinematheque’s flagship event, the Jerusalem Film Festival, suffered.

Noa Regev, at just 32, took control of the reins at a troubled time for the city’s integral cinematic institution. Her predecessor, Sundance executive Alesia Weston, had left the job in less than a year. The body’s budget deficit then was 11 million shekels ($3.2 million). In just seven months as head, Regev oversaw the Cinematheque reaching a balanced budget and tried to bring the festival back to its past glory. She amassed a respectable line-up, an impressive list of guests (including name directors Park Chan-Wook and Spike Jonze) and the promise of festivities.

Then real life struck back. The kidnap and murder of three Israeli teenagers snowballed into an Israel-Palestine crisis the likes of which hadn’t been seen for years. Air raid sirens became a regular sound across Jerusalem and Tel Aviv; there was a possibility of the Hamas bombing the very airport the festival’s guests would have landed in.

But festival continued, albeit in a slightly muted fashion — among the last minute changes was a masterclass with Spike Jonze, canceled less than 24 hours before the event was scheduled to take place.

Still, the festival never came to a halt. Towards the end of the event, Indiewire sat down with Regev to look back at the craziness of the last month. She looked tired — as all festival heads look on the closing day — but otherwise unruffled and satisfied.

Are you happy with the way the festival has turned out?

Are you happy with the way the festival has turned out?

Yes! It wasn’t what we had planned, as you may know. We had a beautiful plan for the festival. We came up with many new initiatives; you saw only some of them. The situation made us reconsider some things. We decided to at least continue the festival, screen the films, and bring the people. To maintain an open atmosphere. However, some of the festivities were canceled. And some people canceled on us.

Ultimately, there were fewer people than we could have had. But, because of the circumstances, it ended up becoming a different kind of festival. An event where people from all over Israel — people from the cultural life here — came together and had an open dialog about the situation. I really believe that cinema has an ability to open new perspectives, not just about the turbulent situation right now but also about life, about anything. I think that specifically in days like these — terrible days — are the time for people to see intelligent cinema and to acquire various perspectives.

Perhaps it’s important to continue living one’s life during a crisis? Showing that you are not afraid and won’t stop doing the things you love sends out a strong message.

That is a strong message but we must draw a line here: it’s not an escapist message. I’m not proclaiming, “Come to the festival and forget everything!” A few people said to me, “Instead of running to a shelter, I’m running between films and that’s good for me.” Of course, some people can use [this festival] as a relief and it’s not a bad thing. Because some people need an event like this. But it’s not escapist. It’s a place where people think, feel, open hearts and minds to each other and to the world. That’s important.

There’s a difference between temporary reprieve and willful avoidance. Do you think people are ignoring the events taking place nearby?

We are not ignoring it at all. Some of the Israeli filmmakers were on stage a few days go and made a moving statement about the situation. Our job is to give all the filmmakers who participate here a platform. We can do that, first and foremost, through their films. But also, they are participants and have a unique place in the festival. We are obliged to give our filmmakers the right platform to say what they want to say.

Is there any instance from the last week that jumps out at you where the art spoke to the people and they responded?

In many ways, it was not the festival we planned. Yet, there were many important and profound moments. For example, the screening of the film about Abie Nathan, [“The Voice of Peace”]. When it ended, all the people just stood and clapped. This is a guy who decided to do something for the sake of peace. He built a boat. He called it The Voice of Peace; it was a free radio — a pirate radio — and transmitted all over the Middle East because it was outside the borders of Israel. He didn’t even talk about politics over the radio. He just got the best music, the coolest music and played it. It’s a very inspiring story and people reacted to it. It brought them to their feet. And right after the screening, we had an air raid siren, to remind us of what times we were living in.

How did you convince outsiders that — morbid as it sounds — air raid sirens were not the end of the world and they should still come to the event?

How did you convince outsiders that — morbid as it sounds — air raid sirens were not the end of the world and they should still come to the event?

First, I had discussions with guests [over] whether they should cancel. Some of them decided to, but not a lot. It’s a personal decision and no one can interfere with it. What I could tell them — and did — is that we really wanted them to be here, that if we thought it was unsafe for them we wouldn’t have invited them. But I can respect a decision made not to come at a time like this. That said, I think whoever came found it very interesting.

Everyone should decide for themselves. In fact, I think it was more interesting than a regular festival. People who came here were interested in exploring the culture. Being in a festival during a warzone and hearing what people here have to say…if you’re not afraid, it’s an amazing experience.

Speaking of warzones, did you feel any obligation to acknowledge the other side while putting the line-up together? Did you want the festival to reflect the state of Palestinian life as well?

We were very interested in bringing Palestinian filmmakers and films. But, unfortunately, it’s become impossible in the last few years due to the concept of normalization. I personally met people and invited them; the Palestinians would say, “I’m sorry. It’s not against you personally. But if I come [to the festival] then I’m accepting Israel. And I’m not.” The question of a boycott is complicated and I’m not going to address it now — whether it’s the right way to tackle a problem or not.

Do you think it’s a personal matter?

Here, I don’t think it’s a personal matter. It’s a political and national matter. It has a lot of political meaning for them [the Palestinian artists]. It wasn’t like this a few years ago. I’m telling you because I know. It was difficult, but not impossible, to have people from Palestine screen their films. I am personally very interested in their cinema — what they are doing — and I try to catch it at international festivals. But I cannot bring them here even though a lot of people in Israel would love to see their films. [The Palestinian artists] cannot do it because they think it is inappropriate.

The festival had a special category devoted to kids; you did your PhD thesis on children’s films. How did you pursue this? Will you continue these activities over the year?

It’s one of my passions. I wrote my PhD dissertation about the theory of genre in cinema and my case study was the children’s film. It opened my eyes to the importance of high quality children’s films. [Childhood] is when people should develop the affection for intelligent and profound cinema. Otherwise, they’re not used to it and it becomes harder for them later on. During the festival, we had a jury comprising six amazing children and they awarded their own prize. This means that children at the age of 10 and 11 can also appreciate good cinema. They just need to have access to it.

So, two months from now, we are opening a young film critics’ club. This will be for children of different communities from all over Jerusalem. We want them to acquire the tools to understand cinema and enjoy more sophisticated art. It should make them fall in love with cinema.

Did you also develop this love for cinema at a young age?

When I was 15, I went to see a film at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque and told myself, “I have to work here. This is where I have to be.” They said, “You’re too young!” But I said “No. I must.”

It was my best job, being an usher. You can put it in the headline. Ever since then, I have been getting away from the theater. I don’t have time.

Time has certainly been short for you at the Jerusalem Cinematheque. When you joined seven months ago, the body was reeling in debt. The previous head had left after just 11 months on the job and the latest edition of the festival had been a disappointment. How did you right this ship?

It’s not only me. It’s important to mention a few things. One is about the financial situation: It was not me. It was the foundations who support the Cinematheque. They went on a very strong recovery plan. It’s true that it’s now our responsibility to maintain the budget we have been granted. But it’s not only me.

Regarding the achievements of the festival: this was certainly not me. It’s a great team of people who came here with passion and commitment. That’s how you do a festival. The people here work double the amount of what they are paid and they don’t give a damn. It’s important for them to promote the cultural life in Israel. Of course I am part of it but it’s a lot of people working for a cause they believe in.

What do you want to do with the Cinematheque over the next year? Any specific goals?

This place should be a platform for the international community of cinema lovers. I feel that Jerusalem has the potential to be a cultural hub, not just because it’s a beautiful city and exotic and whatever. Because of its complexity, there is something about this city that invites intellectual and emotional and social discussions and I have big dreams about it. However, I don’t believe in promises: “Oh! Next year, we’ll have this!”

This place should be a platform for the international community of cinema lovers. I feel that Jerusalem has the potential to be a cultural hub, not just because it’s a beautiful city and exotic and whatever. Because of its complexity, there is something about this city that invites intellectual and emotional and social discussions and I have big dreams about it. However, I don’t believe in promises: “Oh! Next year, we’ll have this!”

Such as?

We do cinematic stand-up comedy once a month. For example, we have added a new tradition where five comedians come on stage. We screen a short scene, then one comes and does comedy about it, and then another comes. I love stand-up comedy. My favorite is…do you know Louis CK?

Yes!

I adore this guy. You wanted to know my dream? I want to bring Louis CK to Jerusalem.

Maybe for a Masterclass?

Of course. It could happen. We just have to work to that.

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.