By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

‘Holy Hell’ Director Will Allen: How He Edited Two Decades of Cult Footage Into A 90-Minute Doc

“Holy Hell” director Will Allen was the Buddhafield’s de facto videographer, recording the group in those lighter moments under the watchful eye of their charismatic leader, known to many as “Michel.”

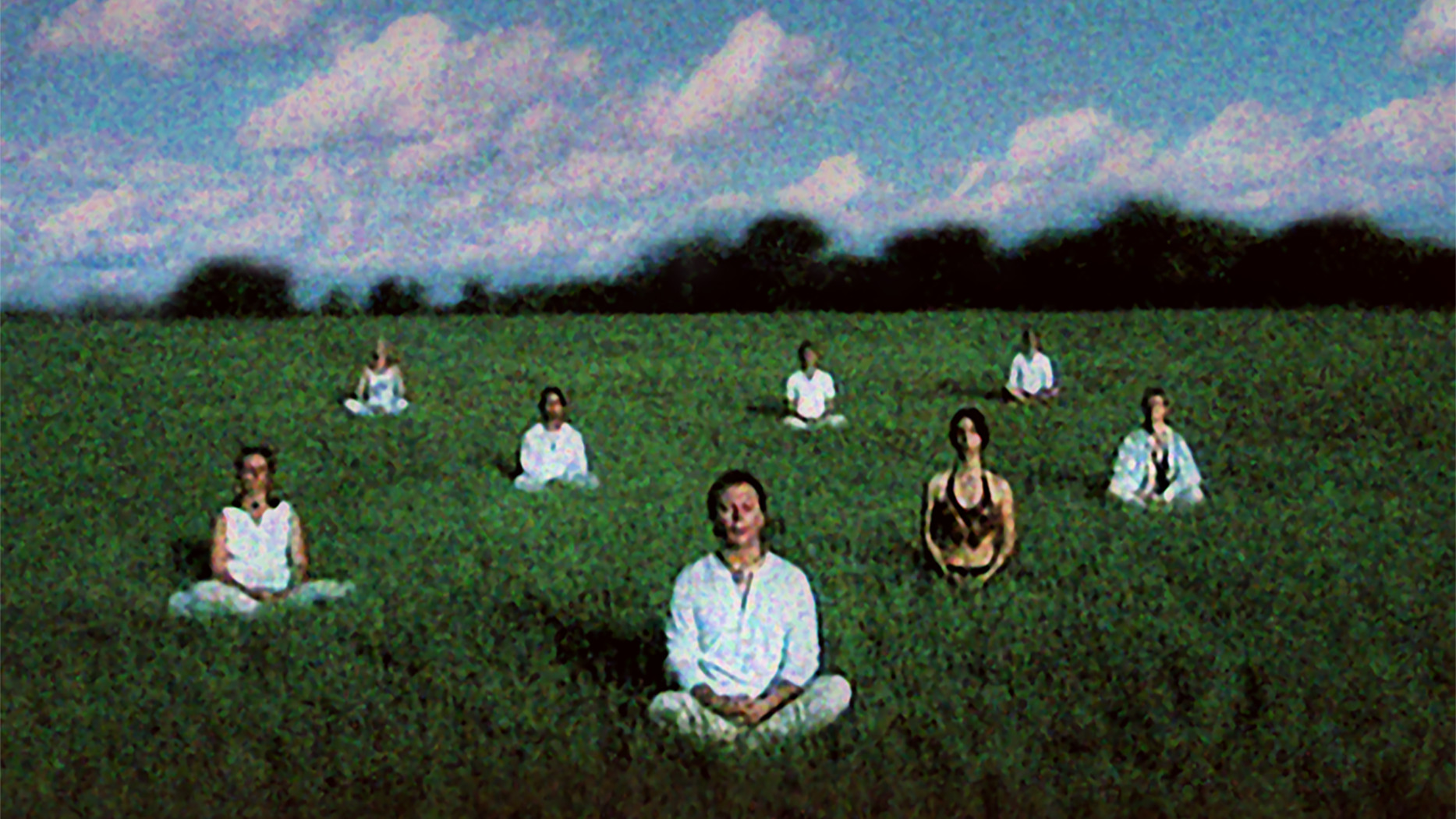

Rather than pious observers silently gathered in a meditation circle, this was nirvana by way of “Baywatch,” a throng of followers frolicking in the surf, the summer sun glistening off the crashing waves of the Pacific. The cleansing nature of this spiritual faction is emphasized at the outset, both to its members in the footage and to the “Holy Hell” audience watching everything unfold. But as Allen shows from an insider’s perspective, disease can come from standing water.

Thirty years later, after fully removing himself from the group, Allen’s documentary gathers that archival footage alongside personal testimony from other former members. After spending most of his adult life in the spiritual wake of a manipulative leader, Allen began the painstaking process of culling these interviews and archival footage down from decades to a handful of reels. Through a combination of their stories, the film gradually conveys the full picture of what shaped their all-encompassing involvement, even as this perfect world began to crumble.

In advance of today’s theatrical release of “Holy Hell,” we spoke to Allen about this unique role of being a friend, a filmmaker and a historian, all at the same time.

Especially at the outset of the film, you focus not just on the logistics of the group, but the emotional center of it. Was that just as important to get those feelings across?

I’m very grateful that my cast can call upon that like it was yesterday, like it’s today. They can call upon that sense of love and joy and awe because they carry it within themselves. And they can pull upon the pain and the sadness, because those are right there too.

As you were sitting down with the other former members, were there specific directions that you gave them or was it more turning on the camera and letting them get everything out?

What became my guide was trying not to tell the story in hindsight. So any time one of the characters started telling the story as if they knew the ending – like “Ah, I never would have done that now!” – they couldn’t say that. I had to keep it in the moment and in the chronology of the story. Whenever there was a hint of someone being bitter or too angry or too self-reflecting early on, we would have to take it out because the audience would think, “Well, if you know that, why are you still there?”

We were trying to carry them on the emotional journey. It was hard, because some of the best stuff is that hindsight. But I had to wait until the third act and build the story so we could talk about it, talk about the hurt. Why it’s damaging. What the pain was. Why it happened.

We wanted to be just a little bit ahead of the audience rather than telling them everything ahead of time. That’s not something I really learned in film school. I learned it making this.

One of the biggest tasks you had for the film was condensing a long timeframe. How did you approach showing the passage of time in a way that made sense?

This time, I just showed the year and had a separate card for the amount of years because I really wanted the audience to feel that more than the date. They do need to think for a second, “This is how many years have gone by,” because we’re moving fast.

You’re presenting so many other people’s experiences, but this is your story too. How did you balance your personal connection with everyone else’s?

Originally, I wanted to tell everyone’s story, not mine. That’s what I’ve been doing for so many years, hiding behind the camera and telling other people’s stories. This one, I had to put myself into it.

My story is a little complicated because I lived with [Michel] for 18 years. So the proximity of my experience was completely different. I can talk about what they’re talking about, but they can’t always talk about what I’m talking about, because they didn’t have my experience. Being around him, I consider it being different degrees of closeness and proximity and damage. Some people on the periphery don’t get hurt because they’re not that involved. All these characters are very involved, but I had a different experience because I lived with him.

We all stay in things, bad relationships or whatever. We don’t know everything. The trick of the matter is that it was really confusing at that time. It took me four, five, seven years to find out what happened and really get the story. None of us really had the whole story at the time. I’m not trying to damn my friends, because we’re all good people. It’s just confusing, is the point.

How important was it for you to focus primarily on the people who were involved and leave that as the primary context for the story?

How important was it for you to focus primarily on the people who were involved and leave that as the primary context for the story?

The first trailer I made – the first attempt at this – had a sociologist, who wasn’t in the group but was aware of it. She was able to speak personally, but very clinically about it. And it was really well inserted in the film. But experts are on every television show now. Dr. Oz has experts. They can end up spoon-feeding the audience what to think. So I decided four years ago that we were going to tell our story ourselves. We weren’t going to have someone who wasn’t there try to speak for us.

It’s interesting that one of the tipping points in many people’s decision to leave the group was an email. You’re talking to the universal experience of finding belonging and then being more connected via the Internet is what helped a lot of you leave.

Which is good for our planet, to have transparency and the Internet. One person said, “It’s hard to do this nowadays because there’s cameras everywhere.” It’s harder to get away with this kind of stuff because everyone has a phone, everyone’s shooting and capturing things. They’re communicating. We know what happens across the world today and we can see it. We have a much better connection to each other, which we didn’t have when we were starting this social experiment.

I always knew I was going to gravitate towards using that footage. I wasn’t sure how. I started editing and I was completely inspired with the idea of the ending and the song. And then I saw my notes and heard my voice memos to myself: I’d had the same exact thought six months ago. Like, “Use this song and say who stayed.”

So it was meant to be, I think. Something else I found that was important to help us illustrate the complexity of the human condition.

“Holy Hell” opens today in New York, Los Angeles and Austin. Screenings will take place in additional cities throughout the month of June.

Stay on top of the latest breaking film and TV news! Sign up for our Festivals newsletter here.

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.