By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

How the Team Behind ‘Unfriended’ Pulled Off the Most Ingenious Horror Film in Years

Nigel M. Smith

Let’s face it — the majority of horror films released by studios nowadays are neither all that scary or particularly creative. Universal’s current micro-budget hit “Unfriended,” written by Nelson Greaves and directed by Leo Gabriadze, is both.

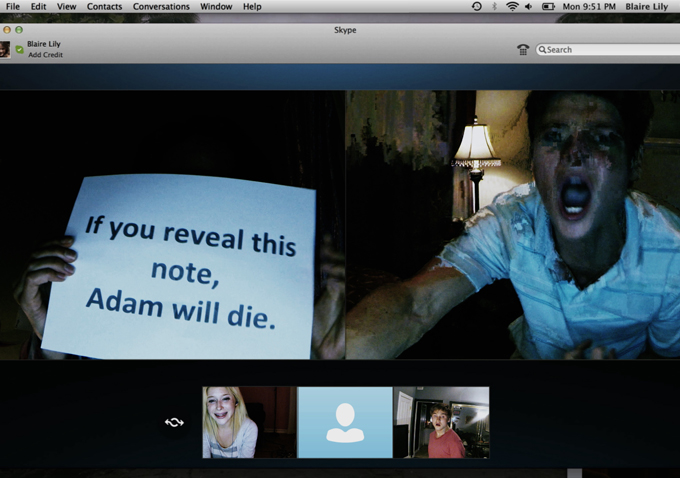

Dreamed up by “Wanted” director Timur Bekmambetov, “Unfriended” plays out entirely on a MacBook screen, where six high school students — plus one sinister seventh party — group chat on Skype on the one-year anniversary of their classmate Laura Barns’ suicide. When the mystery user claims to be Barns, the teens start dying, one by one.

The ingenious execution of “Unfriended” (who knew static webcam images could induce suspense?) hasn’t gone unnoticed by film critics, many of whom embraced the film prior to its theatrical launch last week — a rarity for the horror genre. For a roundup of the positive notices, go here.

So how did Greaves and Gabriadze pull “Unfriended” off? Indiewire called up the pair to learn about the making of the film. “Unfriended” is currently playing nationwide.

How did you two map out the visual approach to the film? Did you really have a specific plan going into production?

How did you two map out the visual approach to the film? Did you really have a specific plan going into production?The second part was how do you put it all together in post. A lot of credit goes to Parker Laramie, who was one of the initial editors on this film, who designed this very complicated system that every editor we’ve shown it to since has said, “This is the most horrendous, frightening Avid timeline I have ever seen.” At times there were literally 30 and 40 layers to the actual timeline, and we very much approached that part of it like an animation, as a bunch of elements working at play together.

The other thing is, so much of the film was written in post, in terms of all of the conversations, the chats, the iChats. So much of that was written by us sitting in front of the Avid saying, “Okay, how else can we do this? How can we improve this? How can we make this more tense? Where else can we take Blaire? How can we deepen this?”

The other thing is, so much of the film was written in post, in terms of all of the conversations, the chats, the iChats. So much of that was written by us sitting in front of the Avid saying, “Okay, how else can we do this? How can we improve this? How can we make this more tense? Where else can we take Blaire? How can we deepen this?” You briefly brought up the fact that your cast acted alone in these rooms for upwards of 80 minutes. That sounds exhausting for your actors.

You briefly brought up the fact that your cast acted alone in these rooms for upwards of 80 minutes. That sounds exhausting for your actors.READ MORE: The Death-by-Skype Horror Movie ‘Unfriended’ is an Unlikely Critical Hit

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.