By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Why Wim Wenders Thinks His Older Films Would Be Flops Today

Anya Jaremko-Greenwold

New York City’s own IFC Center is currently hosting the first leg of German auteur Wim Wenders’ major touring retrospective, “Wim Wenders: Portraits Along the Road,” with Wenders himself set to appear at select screenings for post-screening discussions. Following the IFC launch, the films will then travel to 15+ cities around the country.

For decades, much of Wenders’ work went unseen; it was unavailable due to unresolved rights clearances or poor quality. But Wenders has been faithfully restoring his older films, upgrading the quality and making them permanently accessible to the public. Now is your chance to see his classics on the big screen. A shortened version of “Until the End of the World” was released in theaters in 1991 and critically panned; but this retrospective has the 4.5 hour Director’s Cut, which is infinitely better. It’s the version Wenders intended.

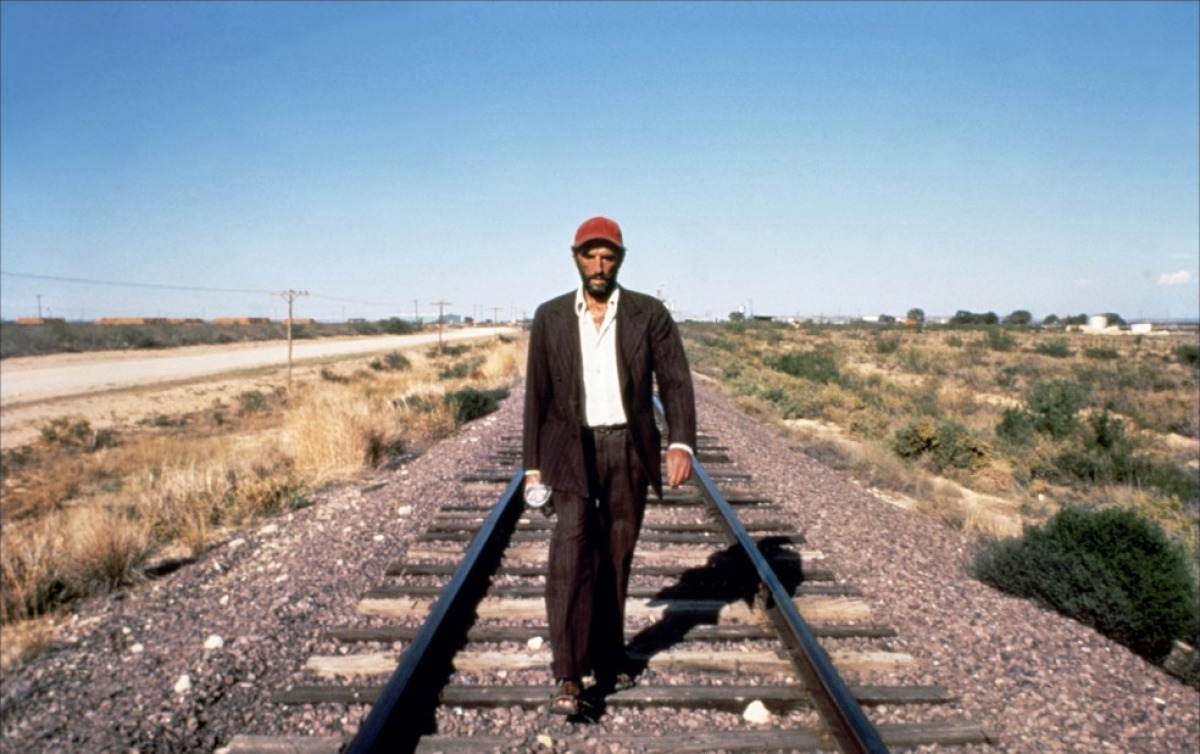

In more recent years, Wenders has turned to the documentary, a genre he believes affords him more creative freedom. This retrospective spans his entire 40-year career, from his earliest road movies (“Kings of the Road,” “Alice in the Cities,”) to the arthouse films of the 80s that elevated him to international acclaim (“Wings of Desire,” “Paris, Texas”) to his documentaries (“Buena Vistal Social Club,” “Pina”). There will also be a sneak peak at Wenders’ surprising latest project, a 3D character drama starring James Franco called “Every Thing Will Be Fine.”

Indiewire spoke with Wenders about how radically the film industry has changed in the past few decades. Some of the spontaneity has gone out of filmmaking; now it’s more of a business, less of an art form. Wenders is disappointed in how filmmakers have progressed (or not progressed) with 3D technology. At this point, the film industry craves “security”—everyone wants to know how a film is going to turn out before they make it or fund it. The time for wistful projects like Wenders’ “Wings of Desire,” made in 1987 with no script and nothing but a simple, dreamy vision, has come and gone. But we still have Wenders’ films, thankfully restored and available to savor for years to come.

Indiewire spoke with Wenders about how radically the film industry has changed in the past few decades. Some of the spontaneity has gone out of filmmaking; now it’s more of a business, less of an art form. Wenders is disappointed in how filmmakers have progressed (or not progressed) with 3D technology. At this point, the film industry craves “security”—everyone wants to know how a film is going to turn out before they make it or fund it. The time for wistful projects like Wenders’ “Wings of Desire,” made in 1987 with no script and nothing but a simple, dreamy vision, has come and gone. But we still have Wenders’ films, thankfully restored and available to savor for years to come.

Even if you’re a big name director?

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.