By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Wally Pfister Turns to Directing With ‘Transcendence.’ Here Are 15 Other Cinematographers Turned Directors.

Max O'Connell

Wally Pfister made a name for himself as one of the top cinematographers in Hollywood over the past decade, shooting Bennett Miller’s “Moneyball,” Lisa Cholodenko’s “Laurel Canyon,” and the films of Christopher Nolan, culminating with his Oscar win for “Inception.” But with “Interstellar,” Nolan has to do without Pfister for the first time since his debut, “Following,” as his regular DP has greater ambitions.

Pfister’s directorial debut “Transcendence” hits theaters on April 17. It’s a highly ambitious, fascinating concept, but it remains to be seen whether Pfister has a shot at a long-term career as a director. In anticipation for that project, here are fifteen major cinematographers who tried their hand at directing, with varying results. [Just a quick note: this list doesn’t include directors who serve as their own cinematographers, such as Steven Soderbergh or Robert Rodriguez.]

Mario Bava

Cinematography Background: Bava got his start working with none other than Italian Neorealism master Roberto Rossellini, shooting his early shorts “The Bullying Turkey” and “Lively Teresa” in 1939. He spent the next two decades as a cinematographer in the Italian film industry, working with notable filmmakers such as Vittorio De Sica (“It Happened in the Park,” co-directed by Gianni Franciolini), Raoul Walsh (the American/Italian co-production “Esther and the King”), Jacques Tourneur (“The Giant of Marathon,” which he did uncredited directing on). Perhaps his most notable film as a cinematographer is the Steve Reeves sword-and-sandals hit “Hercules.” Bava became known for his gifts with optical trickery, something that would serve as one of his calling cards as a filmmaker.

Notable Films Directed: “Black Sunday,” “Black Sabbath,” “The Girl Who Knew Too much,” “Blood and Black Lace,” “Planet of the Vampires,” “Kill, Baby, Kill!,” “Twitch of the Death Nerve” (aka “Bay of Blood” and about fifteen other alternate titles)

How Did He Do?: Pretty spectacular. Bava’s lurid, visually striking horror films paved the way for the likes of Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci in the 1970s, with “Blood and Black Lace” often regarded as the first giallo film. “Black Sunday,” influenced the look of Francis Ford Coppola’s “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” thirty-two years after its release, while Dan O’Bannon’s script for “Alien” borrows elements from “Planet of the Vampires” wholesale. And anyone who ever enjoyed a slasher film, guiltily or not, owes it to themselves to check out Bava’s spectacularly nasty “Twitch of the Death Nerve” (on Netflix as “Bay of Blood”), from which “Friday the 13th Part 2” steals one of the more memorable death scenes.

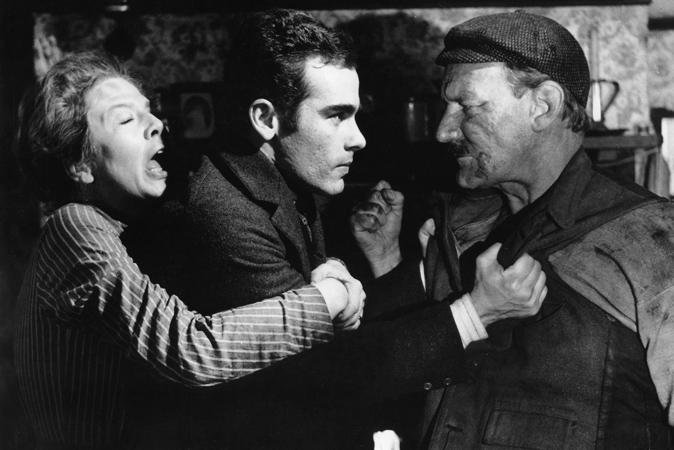

Jack Cardiff

Cinematography Background: Michael Powell’s films are known for their sensuous, almost impossibly gorgeous looks, and Jack Cardiff is partly responsible for three of their best works. Cardiff shot “A Matter of Life and Death” (aka “Stairway to Heaven”), with its spectacular, imaginative view of the afterlife, “Black Narcissus,” for which he won the Oscar for Best Cinematography, and “The Red Shoes,” surely among the most beautiful-looking movies ever made. He also worked for such A-list directors as Alfred Hitchcock (“Under Capricorn”), John Huston (“The African Queen”), Joseph L. Mankiewicz (“The Barefoot Contessa”), and King Vidor (“War and Peace”). He eventually returned to cinematography in the 80s, shooting action flicks like “Conan the Destroyer” and “Rambo: First Blood Part II.”

Notable Films Directed: “The Story of William Tell” (unfinished), “Scent of Mystery,” “Sons and Lovers,” “Dark of the Sun”

How Did He Do?: Not bad. Cardiff had a rough start on his directorial debut, “The Story of William Tell,” a passion project of Errol Flynn’s that would have been the first independent film in CinemaScope, had it not been for finance problems that would ruin Flynn. Cardiff directed a few other smaller productions before shooting 1960’s “Scent of Mystery,” the first film shot in Smell-O-Vision, another disaster as the scent cards didn’t work properly at the premiere and negative word-of-mouth spread before the problem could be fixed. Cardiff’s directorial career wasn’t a total boondoggle, though: his other 1960 film, the D.H. Lawrence adaptation “Sons and Lovers,” was an Academy Award nominee for Best Picture, while Cardiff himself was nominated for Best Director alongside Billy Wilder (“The Apartment”) and Alfred Hitchcock (“Psycho”). Most of Cardiff’s subsequent directorial work didn’t make many waves, but 1967’s “Dark of the Sun” has fans in Martin Scorsese, who calls it a guilty pleasure, and Quentin Tarantino, who used its music in “Inglourious Basterds.”

Michael Chapman

Cinematography Background: After working as a camera operator on “The Landlord,” “The Godfather” and “Jaws,” Chapman became one of the go-to guys for photographing grungy locations and seedy underbellies in the 1970s. Working with directors like Hal Ashby (“The Last Detail”), Philip Kaufman (“Invasion of the Body Snatchers”) and Paul Schrader (“Hardcore”), Chapman’s best work is featured in the two films he shot for Martin Scorsese (not counting “The Last Waltz,” which has several cinematographers): “Taxi Driver,” with its portrait of the scuzziest sides of New York in the 1970s, and “Raging Bull,” which beautifully contrasted grandiose camera movements in the ring and fly-on-the-wall compositions in the domestic scenes. Following his work as a director, Chapman mostly shot comedies like “Ghostbusters 2,” “Quick Change,” and “Kindergarten Cop”, but he did get a few more highlights with the strikingly lit “The Lost Boys” and for his memorable work in Chicago on “The Fugitive” and “Primal Fear.”

Notable Films Directed: “All the Right Moves,” “Clan of the Cave Bear,” “Annihilator,” “The Viking Sagas”

How Did He Do?: Not great. Chapman’s most well-known film as a director is “All the Right Moves,” the Tom Cruise football drama that capitalized on the success of “Risky Business” by being the first film to put Cruise’s name above the title. It’s a pretty cliched piece of work, though it has a fan in Rose McGowan’s character from “Scream” (who notes that pausing it at the right moment gives a glimpse of Cruise’s penis). His follow-up, “The Clan of the Cave Bear,” is a bit more ambitious, with Daryl Hannah starring as a Cro-Magnon woman raised by Neanderthals, with most dialogue done in sign language with subtitles. The film flopped, however, and Chapman’s only other films as a director were the TV movie “Annihilator” and the barely-known “The Viking Sagas.”

Jan de Bont

Cinematography Background: The Dutch cinematographer’s first notable credit was on Andy Warhol’s “Blue Movie,” but his most fruitful collaboration started three years later with Paul Verhoeven’s 1973 film “Turkish Delight.” de Bont would later shoot “The Fourth Man,” “Flesh + Blood” and “Basic Instict” for Verhoeven, along with genre hits such as “Cujo,” “Flatliners” and Ridley Scott’s extremely stupid but pretty “Black Rain.” He had his share of duds, from both of Michael Chapman’s major films as a director to “Shining Through,” with Bill Cosby’s disastrous “Leonard Part 6” as the lowlight. But de Bont deserves credit for shooting “Die Hard,” which, on top of being one of the signature action films of the 80s, is absolutely gorgeous.

Notable Films Directed: “Speed,” “Twister,” “Speed 2: Cruise Control,”The Haunting,” “Lara Croft Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life”

How Did He Do?: Good start, rough finish. de Bont’s best film as a director was his first, “Speed,” the premise of which (“‘Die Hard’ on a bus”) is too good to screw up too badly, and benefits from game performances by Keanu Reeves, Sandra Bullock and Dennis Hopper. Things started to turn, however, with his not as critically admired but wildly successful follow-up, “Twister,” before he returned to the runaway vehicle well for the much-mocked “Speed 2: Cruise Control.” de Bont’s hacky remake of “The Haunting” didn’t much help, grossing less than $100 million domestically on an $80 million budget, but the final nail in the coffin of his directing career came with the little-loved “Lara Croft Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life.” Aside from work as a cinematographer on the Dutch film “Nema aviona za Zagreb” and as an executive producer on “The Paperboy,” de Bont hasn’t made a film since.

Tom DiCillo

Cinematography Background: Tom DiCillo earned permanent indie cred for being the first cinematographer to work with Jim Jarmusch. After shooting Jarmusch’s post-film school feature “Permanent Vacation,” DiCillo worked with the king of indie deadpan cool on his breakthrough “Stranger Than Paradise,” with its spectacularly drab, lo-fi composition suiting its listless hipster characters perfectly. DiCillo would soon move on to directing, but not before serving as DP for the first of Jarmusch’s “Coffee and Cigarettes” shorts, “Strange to Meet You” with Roberto Benigni and Steven Wright.

Notable Films Directed: “Johnny Suede,” “Living in Oblivion,” “Box of Moonlight,” “The Real Blonde,” “Double Whammy,” “Delirious,” “When You’re Strange”

How Did He Do?: Very well. DiCillo wasn’t too satisfied with Brad Pitt’s work in his debut film “Johnny Suede,” but the film won the Golden Leopard at the Locarno Film Festival. His next and best-known film, “Living in Oblivion,” is one of the funniest movies ever made about filmmaking, starring Steve Buscemi as a filmmaker working through egotistical stars (James LeGros), insecure actors (Catharine Keener), and temperamental dwarves (Peter Dinklage in his first film) while trying to make an independent film. Most of DiCillo’s subsequent work wasn’t as well-received, but his 2006 paparazzi satire “Delirious” garnered strong reviews, as did his solid 2009 The Doors documentary “When You’re Strange.”

Ernest R. Dickerson

Cinematography Background: Few filmmakers who emerged from the 1980s were as exciting as Spike Lee, and Ernest R. Dickerson’s work is a large part of it. When film fanatics picture Lee’s films, they think of the bright colors and depiction of heat in “Do the Right Thing,” or the sudden shift from stark black-and-white to Vincente Minnelli colors in “She’s Gotta Have It.” Dickerson shot all of Lee’s films up to and including “Malcolm X,” as well as the Eddie Murphy stand-up film “Raw,” John Sayles’s “The Brother from Another Planet,” and Jonathan Demme’s criminally underseen “Cousin Bobby” before embarking on his own directing career.

Notable Films Directed: “Juice,” “Surviving the Game,” “Bulletproof,” “Blind Faith,” “Bones,” “Never Die Alone”

How Did He Do?: Dickerson did reasonably well the first time out with his 1992 youth-in-Harlem movie “Juice,” which featured memorable early performances from Tupac Shakur and Omar Epps. The other films on his resume, however, are pretty much duds: the little-loved Rutger Hauer/Ice-T thriller “Surviving the Game,” the Adam Sandler/Damon Wayans buddy action-comedy “Bulletproof,” the awful Snoop Dogg-starring horror movie “Bones,” and a DMX vehicle called “Never Die Alone.” Still, Dickerson’s work on TV helps even it out: his TV movie “Blind Faith” drew accolades for its script and Charles S. Dutton’s performance, and his work on David Simon’s beloved series “The Wire” drew heavy praise from Simon himself, who’s worked with Dickerson since on “Treme.”

Christopher Doyle

Cinematography Background: The word “lush” applies to Christopher Doyle’s work more than that of nearly any other contemporary cinematographer. The outspoken Australian cinematographer has turned out some of the most gorgeous films of the past two decades, with his work with Wong Kar-wai (“Days of Being Wild,” “Chungking Express,” “Ashes of Time,” “Fallen Angels,” “Happy Together,” “In the Mood for Love,” and “2046”) standing out in particular. Outside of his work with Wong, he’s worked on some of the best-looking films in the careers of Zhang Yimou (“Hero”), Barry Levinson (“Liberty Heights”), and Gus Van Sant (“Paranoid Park,” the useless but pretty-looking remake of “Psycho”).

Notable Films Directed: “Away With Words,” “Warsaw Dark”

How Did He Do?: Don’t quit your day job. Doyle’s debut “Away With Words” wasn’t received with much more than a shrug when it debuted at Cannes’ Un Certain Regard section in 1999, and his follow-up “Warsaw Dark” was barely seen. The best known film directed by Doyle at this point is “Porte de Choisy,” his mediocre segment of the wildly uneven omnibus film “Paris, je t’aime.”

William A. Fraker

Cinematography Background: A six-time Oscar nominee (without a single win), Fraker received accolades aplenty for his work on “Heaven Can Wait,” “Looking for Mr. Goodbar” and “WarGames.” But his best work as a DP comes from his work in the late 60s on the crisp Steve McQueen thriller “Bullitt,” on the madcap satire “The President’s Analyst,” and, most notably, on Roman Polanski’s horror masterpiece “Rosemary’s Baby.” The last of the bunch saw Fraker’s distinctive look blending reality with the look of deeply unsettling dreams, and that’s not even including the horrifying dream sequence that caps off the film’s first act.

Notable Films Directed: “Monte Walsh,” “A Reflection of Fear,” “The Legend of the Lone Ranger”

How Did He Do?: Fraker made a solid debut in 1970 with the James Coburn and Jack Palance-starring western “Monte Walsh,” about aging cowboys at the end of the Wild West era. But Fraker’s follow-up, the horror film “A Reflection of Fear,” didn’t get much play, and his 1981 film “The Legend of the Lone Ranger” was a notorious bomb surrounded by bad publicity, both for its general lousiness and for the producer’s attempt to block original Lone Ranger Clayton Moore from appearing in costume at events (something he had done for years) so as not to confuse audiences into thinking the aging actor would reprise his role. The film’s failure effectively ended Fraker’s directing career, and he returned to cinematography to shoot a couple of winners (“The Freshman,” “Tombstone”) and a whole lot

of losers (“Street Fighter: The Movie,” “The Island of Dr. Moreau,”

“Town & Country”) before his retirement in the early 2000s.

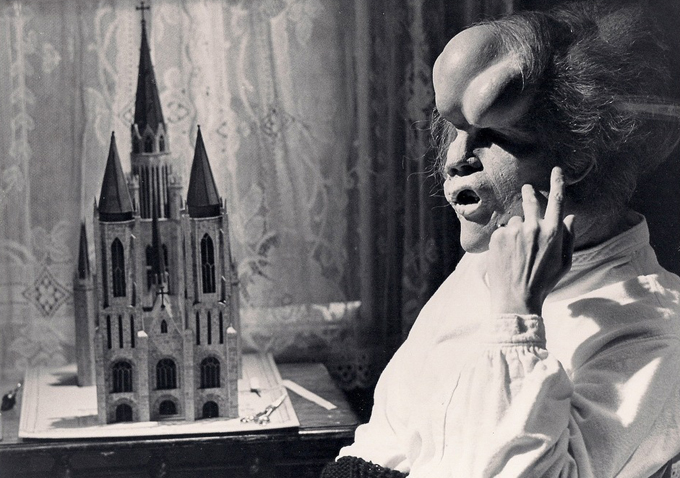

Freddie Francis

Cinematography Background: Francis began his career as a camera operator on films by Powell and Pressburger (“The Elusive Pimpernel,” “Tales of Hoffman”) and John Huston (“Beat the Devil,” “Moby Dick”) before becoming a go-to cinematographer in the British New Wave of the 1960s. Francis shot films for Jack Clayton (“A Room at the Top,” “The Innocents”) and Karel Reisz (“Saturday Morning and Sunday Night”), culminating in his Oscar win for shooting none other than fellow cinematographer Jack Cardiff’s “Sons and Lovers.” After a decade and a half of working as a director, Francis took up DP work again on David Lynch’s gorgeous Victorian biopic “The Elephant Man,” his best work. He followed that up with “The French Lieutenant’s Woman,” “Dune,” another Oscar win for for “Glory,” “Cape Fear,” and an excellent swan song on Lynch’s “The Straight Story.”

Notable Films Directed: “The Evil of Frankenstein,” “Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors,” “The Deadly Bees,” “Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny and Girly,” “Dracula Has Risen From His Grave,” “Trog,” “Tales from the Crypt,” ““Son of Dracula”

How Did He Do?: Francis’s directing career was a bit all over the place. After an inauspicious debut with “Two and Two is Six,” a romance starring George Chakiris, Francis embarked on a career directing horror movies for British horror studios such as Hammer and Amicus. Francis directed a few of the better entries in the long-running Hammer Frankenstein and Dracula series (“The Evil of Frankenstein,” “Dracula Has Risen From His Grave”), as well as the cult horror-comedy “Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny and Girly” and a number of “Dead of Night”-style horror portmanteau films, including the spectacularly-named “Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors” and “Tales from the Crypt,” the latter of which was based on the EC Comics series turned into the popular horror series (which Francis directed an episode of). But his career had some real dogs as well, like the silly “The Deadly Bees” and the notoriously awful “Trog,” a low-budget caveman horror movie starring Joan Crawford in her final screen role.

Karl Freund

Cinematography Background: Karl Freund was one of the go-to directors for the German Expressionist movement, starting on early films of Robert Wiene, F.W. Murnau, Fritz Lang and Ernst Lubitsch, then graduating to shooting major films of the era like “The Golem,” Murnau’s “The Last Laugh,” and Lang’s “Metropolis.” His mastery of shadows and light made him an ideal candidate for Universal Horror when he emigrated to American in the 1930s, moving on to shoot Bela Lugosi in both Tod Browning’s “Dracula” and “Murders in Rue Morgue.” Freund moved on to larger prestige pictures later, winning an Oscar for the cinematography on “The Good Earth” and working with the likes of George Cukort (“Camille”), Victor Fleming (“Tortilla Flat,” “A Guy Named Joe”) and John Huston (“Key Largo”) before becoming the regular cinematographer on “I Love Lucy,” shooting 148 out of 181 episodes.

Notable Films Directed: “Dracula” (uncredited), “The Mummy,” “Mad Love”

How Did He Do?: Freund didn’t get credit for his first U.S. directing job – “Dracula” director Tod Browning was in a foul mood during most of the shoot, due to his alcoholism and the death of his friend and originally planned leading man Lon Chaney, so Freund would direct scenes whenever Browning left the set. Universal was apparently happy with his work, because they gave him one of their next big projects, 1932’s “The Mummy” with Boris Karloff. All those years of working in atmospheric terror paid off, because “The Mummy” is one of the best horror films of the era. But with the exception of his final film as a director, the creepy 1935 Peter Lorre shocker “Mad Love,” Freund’s subsequent films as a director aren’t widely known, and he soon turned back to shooting other people’s films.

Janusz Kaminski

Cinematography Background: Steven Spielberg worked with a number of great cinematographers throughout his career (Vilmos Zsigmond, Douglas Slocombe, Allen Daviau), but after he hired Janusz Kaminski for 1993’s “Schindler’s List,” he never looked back, working with him on all of his live-action films since. Kaminski won Oscars for both the gorgeous black-and-white of “Schindler’s List” and the stunning desaturated look of “Saving Private Ryan,” but his breathtaking use of chiaroscuro in the Spielberg sci-fi films “A.I.: Artificial Intelligence” and “Minority Report” is just as strong, not to mention some of the incredible images in recent Spielberg epics “War Horse” and “Lincoln.” Kaminski has some impressive credits outside of Spielberg’s filmography as well, from the no-brainers (“The Diving Bell and the Butterfly”), to the less characteristic but equally inspired (“Jerry Magure,” “Funny People”).

Notable Films Directed: “Lost Souls,” “Hania”

How Did He Do?: Very, very poorly. After winning his second Oscar for “Saving Private Ryan,” Kaminski made his directorial debut with the 2000 horror movie “Lost Souls” starring Winona Ryder and Ben Chaplin. The film was delayed several times, first because of the close proximity of a similar “end of the world” horror movie, “End of Days,” then because of a conflict with the release of “Scream 3.” When the film finally debuted, it came in a distant third-place at the box office behind “Meet the Parents” and “Remember the Titans” in their second and third weeks, respectively. Even ignoring financial disappointment, “Lost Souls” was eviscerated by critics as a good-looking but inert and derivative horror movie. Kaminski’s second film, “Hania,” was barely seen, and his upcoming independent film “American Dream” doesn’t seem to have a release date yet.

Nicolas Roeg

Cinematography Background: After starting as a camera operator and second unit photographer (notably on “Lawrence of Arabia,”), Roeg shot Roger Corman’s striking adaptation of Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Masque of Red Death.” Roeg’s gifts with lurid colors got him noticed by Francois Truffaut, who picked him to shoot his only English-language film, the flawed but fascinating (and beautiful-looking) adaptation of “Fahrenheit 451.” He then finished his brief but memorable cinematography career shooting three notable films from British New Wave directors: Richard Lester’s “Petulia” and “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” and John Schlesinger’s “Far From the Madding Crowd.”

Notable Films Directed: “Performance,” “Walkabout,” “Don’t Look Now,” “The Man Who Fell to Earth,” “Insignificance,” “The Witches”

How Did He Do?: Terrific, at least for a little while. Roeg emerged as one of the most exciting and adventurous British directors of the 1970s with his influential gangster/rocker film “Performance.” For a director with a background in cinematography, he became as well known for his jarring cross-cutting and editing techniques as for his stunning compositions, as evidenced by the brilliant Australian drama “Walkabout” and the bizarre, terrifying thriller “Don’t Look Now,” which features one of the most memorable sex scenes in film history as Roeg cuts back and forth between Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie making love and dressing for an outing afterwards. Roeg made another landmark film with the odd David Bowie science fiction film (and clear “Under the Skin” inspiration) “The Man Who Fell to Earth” before his career became much spottier in the 80s and 90s. Still, there are a few gems from Roeg’s late career, including his 1985 musing on celebrity and identity, “Insignificance,” and his 1990 adaptation of Roald Dahl’s “The Witches.”

Barry Sonnenfeld

Cinematography Background: Before Roger Deakins, Barry Sonnenfeld was the man who helped bring the Coen Brothers’ unforgettable images to the screen. Sonnenfeld’s first major film as a cinematographer was “Blood Simple,” which showed a remarkably assured eye for capturing the darkest corners of the world. Sonnenfeld showed his versatility shooting the Coens’ next two films, the outlandish madcap comedy “Raising Arizona” and the heavily stylized yet restrained and mournful noir “Miller’s Crossing.” Sonnenfeld got a few crowd pleasers in there, as well, shooting “Big,” “Throw Mamma From the Train,” and two of Rob Reiner’s better films, “When Harry Met Sally…” and “Misery.”

Notable Films Directed: “The Addams Family,” “The Adams Family Values,” “Get Shorty,” “Men in Black,” “Wild Wild West,” “Big Trouble,” “Men in Black II,” “RV,” “Men in Black III”

How Did He Do?: Sonnenfeld started off strong. Combining the exaggerated style of the Coens with the crowd-pleasing notions of some of his other projects, Sonnenfeld debuted with a fun adaptation of “The Addams Family,” which looked terrific and featured a great performance from Raul Julia. Following an equally enjoyable sequel (“Addams Family Values”), and a dud Michael J. Fox romance-comedy (“For Love or Money”), Sonnenfeld made his two best films back to back: the Hollywood satire/crime comedy “Get Shorty” and the buddy movie/sci-fi comedy “Men in Black.” Sonnenfeld was on top of the world until he followed up “Men in Black” with another Will Smith-starring genre mash-up, the disastrous “Wild Wild West.” Things got worse on the lousy comedy “Big Trouble,” which was delayed and abandoned because of a plotline involving sneaking a nuclear device onto a plane following the events of September 11th. Sonnenfeld had another financial hit with the lame sequel “Men in Black II” before dropping out a Coen-penned remake of “The Ladykillers” (to be directed by the Coens themselves) and bottoming out with the terrible Robin Williams family comedy “RV.” Sonnenfeld has made a minor comeback, however, first with the well-liked (if short-lived) series “Pushing Daisies,” then with the surprisingly solid “Men in Black 3.”

Haskell Wexler

Cinematography Background: One of the true great cinematographers of American cinema, Wexler first got attention for Elia Kazan’s epic “America, America” before winning an Oscar for “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf,” in which he brought a new sense of realism and starkness that would become an early template for New Hollywood. Wexler next served as cinematographer for Norman Jewison on “In the Heat of the Night” and “The Thomas Crown Affair,” and his eye combined with Hal Ashby’s assured editing helped lift the usually workmanlike Jewison into more thrilling territory. Ashby went on to become a great director in his own right, and he brought Wexler on as his cinematographer for his Dust Bowl-set Woody Guthrie biopic “Bound for Glory” (another Oscar win) and his Vietnam veteran film “Coming Home.” Wexler’s post-70s work isn’t quite as consistent, but he did shoot some of John Sayles’s best-looking, most expressive films, including “Matewan” and “The Secret of Roan Inish.”

Notable Films Directed: “The Bus,” “Brazil: A Report on Torture,” “Medium Cool,” “Latino,” “Who Needs Sleep?,” “Four Days in Chicago”

How Did He Do?: Wexler’s directorial career mostly consists of documentaries covering social justice issues, be it the 1960s Civil Rights movement (“The Bus”), violence under the Brazilian militarist regime (“Brazil: A Report on Torture”), the deadly combination of sleep deprivation and long work days (“Who Needs Sleep?”), or, most recently, the Occupy Movement’s demonstrations against the 2012 NATO summit (“Four Days in Chicago”). Wexler only tried his hands at narrative filmmaking a few times, but he made something truly revolutionary in 1969 with “Medium Cool.” A combination of a fictional story (Robert Forster stars as a TV news cameraman) and real-life events (the disastrous 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago), bringing a new sense of urgency and liveliness as fictional characters meshed with real political upheaval and riots. Pity he didn’t direct fictional films more often (1985’s “Latino” is barely remembered), but then, this kind of confluence often doesn’t even happen once in a lifetime.

Zhang Yimou

Cinematography Background: Zhang Yimou was admitted to the Beijing Film Academy’s Faculty of Cinematography, despite his not having the academic qualifications and being over the age limit, off of the strength of his photography. After studying alongside contemporaries such as Tian Zhaungzhaung (“Horse Thief”) and Chen Kaige (“Farewell My Concubine”), Zhang became a cinematographer at Guangxi Film Studio. Zhang made a name for himself by capturing remarkable images of human conflict against great forces in Zhang Junzhao’s “One and Eight” and Chen’s “Yellow Earth” and “The Big Parade.” Zhang also shot and starred in Wu Tianming’s well-received “Old Well” before he got his shot at directing after Guangxi realized they had few trained filmmakers following the Cultural Revolution.

Notable Films Directed: “Red Sorghum,” “Ju Dou,” “Raise the Red Lantern,” “To Live,” “Hero,” “House of Flying Daggers,” “Curse of the Golden Flower,” “Flowers of War.”

Notable Films Directed: “Red Sorghum,” “Ju Dou,” “Raise the Red Lantern,” “To Live,” “Hero,” “House of Flying Daggers,” “Curse of the Golden Flower,” “Flowers of War.”

How Did He Do?: Easily the strongest filmmaker on this list, Zhang Yimou is responsible for some of the most visually sumptuous films of the past two decades. Zhang’s debut film, “Red Sorghum,” won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, immediately marking him one of the most exciting filmmakers of his generation. It also began a fruitful collaboration with muse (and sometime lover) Gong Li, who starred in his first seven films. Some of those include the astounding tragedy “Ju Dou” and the wildly ambitious anti-authoritarianism film “Raise the Red Lantern,” both of which were shot in three-strip Technicolor long after the process went out of fashion in the West. Both films were banned for a time in mainland China, while his Communist-critical 1994 film “To Live” got Zhang banned from filmmaking for two years. Zhang became less stridently political afterwards (though he’s denied he had any political messages in the first place), making the excellent wuxia films “Hero” and “House of Flying Daggers,” as well as the solid “Curse of the Golden Flower,” which reunited him with Gong. Zhang’s had some trouble in recent years, including the tepid 2011 epic “The Flowers of War” and a heavy fine following his violation of China’s One-Child policy. Yet he remains a major filmmaker, and the teaser for his new film “Coming Home” (coupled with the news of his first Hollywood film, the Robert Ludlum thriller “The Parsifal Mosaic”) gives reason to believe that he’s got a few tricks up his sleeve yet.

Are there any cinematographers we left out? Do you want to make a case for the directorial careers of Rudolph Maté, Gordon Willis, Phedon Papamichael or Sven Nykvist? Let us know.

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.