By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

From Concept to Final Cut: 10 Tips on Making a Documentary

Shipra Harbola Gupta

Earlier this month, the Sundance Institute hosted its first-ever ShortsLab in Los Angeles, dedicated exclusively to conversations about documentary filmmaking. While billed as a conversation about short-form documentary, over the course of the day, most of the discussions that occurred onstage dealt with the genre as a whole — which demonstrates the significance of the oft-cited, yet also ignored notion that run-time aside, the same basic ingredients are always in the mix when a filmmaker is trying to structure his or her story.

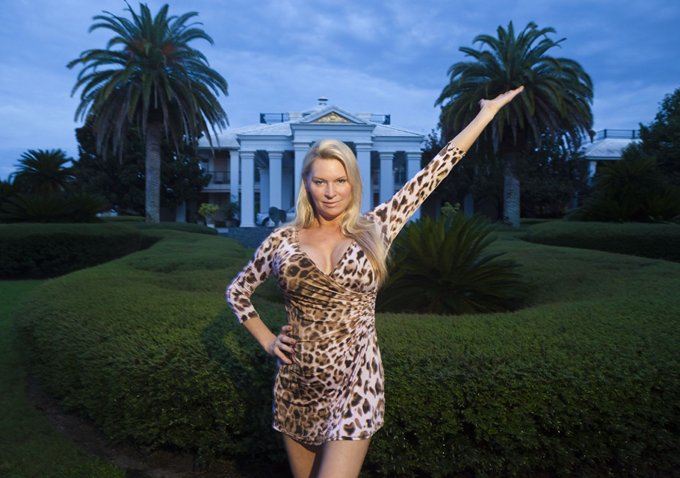

As documentarian Lauren Greenfield (“The Queen of Versailles“) pointed out during the first session of the day, “Story trumps all.”

“There are so many times that the crappiest footage ends up in your film,” Greenfield said. “It’s going to end up in the movie no matter how it looks because the story is the most important thing.”

Greenfield, who is a Sundance Film Festival and Documentary Lab alumnus, sat on the Institute’s first panel of the day, alongside Academy Award-nominated documentarian Kirby Dick (“The Invisible War”). Given the combined breadth of their experience, both cinematic and topical, Greenfield and Dick managed to outline the most crucial aspects of the documentary production process for both short and longform filmmakers.

Below, Indiewire has compiled a collection of Greenfield and Dick’s most salient points and placed them into an outline that roughly mirrors the production timeline from beginning to end:

1. There is a such thing as a “good subject.” It’s someone who wants to participate because he or she also has a stake in the project.

“You want to look for extroverts, you really do. You can make a film about an introvert and it can be interesting, but extroverts make your life a lot easier. [Filming] is something they look forward to and they miss it when [it’s] over. That is a really good sign that you have a good subject.” – Dick

“You have to find that thing that is important to the subject. Like when I was doing ‘Thin,’ at one point the therapist asked Shelly, the main character, ‘Why are you allowing this to be filmed?’ [She was referring to] the therapy; we were in a treatment center for women with very severe eating disorders and we were in the therapy sessions [with Shelly]. And she [Shelly] said, ‘Because I want people to know what it is like to have an eating disorder.’ And he [the therapist] said, ‘Well that is kind of general, who do you want to know?’ And she said, ‘My dad.’ When you’re dealing with eating disorders, the people close to [the victims] have trouble understanding what [their loved ones] are going through. I think you have to search for those things — where they [your subject] has some kind of stake in it too.” – Greenfield

2. You have an idea, but you’re worried it’s not original enough. Stop it, right now.

“I have developed my own way of looking at things, and so I feel like even if it’s a subject that has been explored, I kind of do it in my own way, and that is where the originality comes from. I don’t really believe in original ideas, I think it’s more in the execution. When I pitched [‘Girl Culture’] nobody was interested in it because there had been so much done in gender, and yet it hadn’t really be done photographically that way, even though it had been done in the literary and academic world. People don’t usually get my work until it’s done because it’s kind of like what Kirby said, I’m kind of similar — I don’t really know exactly where it’s going, I work very intuitively, and so, I also don’t know if it will ever become anything. Like I remember when ‘Queen of Versailles’ was at Sundance, a filmmaker [approached me] and he was like, ‘You know, when I saw you six months ago, it sounded like you were in a really bad place and you had a really bad project.’ And that’s kind of how it is when you’re in the middle of it [because when] I went to the Sundance lab people hated it. So I feel like the process is really important. You can’t be thinking about the outcome — whether it’s impact or anything else — while you are working. You have to be happy with that process.” – Greenfield

READ MORE: 9 Tips On How to Make Your First Documentary

3. Keep in mind that the only way to get your documentary idea off the ground is to get access. Without access, you’ve got nothing.

3A. That said, don’t get bent out of shape asking for access.

“Presume you have [access]. Let somebody tell you no. People just assume you know what you’re doing, so they will allow you to do it.” — Dick

4. Lack of access can sometimes make for a story in and of itself.

“I was on the McCain plane during the [last presidential election], and it was at a very tense point in the campaign, after things were starting to fall apart with Sarah Palin. I was there from The New York Times Magazine and the McCain campaign hated [the magazine], so [there] I was, doing a cover story and yet I got no access. I spent a lot of time enraged that I wasn’t getting anything special, but then, one of the reporters from The Washington Post said to me, ‘You know, there is actually a freedom in being in the back of the plane because when you’re in the front of the plane with the candidate, you are one of the trusted people, and there is a kind of implicit agreement about what you will and won’t do.’ I had a kind of freedom coming in and coming out, being in the back of the plane, to just show it like I saw it, with no allegiance to anybody. The picture that ended up being the opening spread of the story was a picture of an empty podium, with the McCain plane behind, and everybody gone. [The story ended up being] about the week before the election and the falling apart of the campaign.” — Greenfield

5. Obtaining story and life rights is not necessary but a signed release from your subjects is.

“It’s good to get them (life rights). It depends on who they are, but I don’t like really bringing up contractual issues. You want a release, so you should absolutely get one every time you shoot and that will pretty much cover you with everything. If you have a subject who is sophisticated and might take issue with what you’ve done, then you’ll probably want to consult an attorney — especially if they are such a central part of the film. More and more, (narrative) films are being made based on documentaries, so if you expect [those rights] and you want [them], [the matter] should be discussed at some point.” – Dick

READ MORE: Making a Living as a Documentary Filmmaker Is Harder Than Ever. Here’s Why

6. When you’re filming there will never be a time when it is “okay” to turn off the camera.

“The biggest challenge is when to turn off the camera. It so often seems as soon as you turn off the camera, you start getting interesting things happening.” – Dick

7. If you’re shooting verité, don’t micromanage your DP or worry about the quality of the footage.

“With film, since I’m directing and not behind the camera, I’ve had to trust the DP. When we’re shooting verité, it’s like when I’m taking pictures, by the time somebody tells you what to shoot, you’ve missed it. They can’t see what you see anyway, so you have to trust what they see.” – Greenfield

“When it comes to verité, audiences do not care about the quality of the image. It’s incredible. Oftentimes, a lower quality makes it seem more real.” – Dick

8. Start cutting right away.

“I think it’s really important to start cutting scenes, if you have [them], just to look at them [and] show them to people. Sometimes you think a subject is good and audiences don’t respond to it, or the reverse. I mean, a secondary subject in a scene, suddenly people are going, ‘Huh, I’m really interested in that person,’ and [you go], ‘I wasn’t even structuring the film that way.’ Editing also shows you what you are missing in your coverage.” – Dick

9. In most cases, the three-act structure rule still applies to documentaries.

“In terms of narrative, one of the things that really helped me was writing screenplays. To understand classic narrative structure is really valuable. I see my films in three-act structure all the time. I mean sometimes, I wish they were in a three-act structure, and they’re not — but I’m always look for [it] because audiences, for better or worse, are very trained to read a film in that way. Ninety-eight percent of your audience wants to see that, and if you’re hitting those beats — I know this sounds like a formula, and it is — audiences are going to be very happy. [Breaking the formula] is a whole other discussion.” – Dick

10. Don’t worry about finding the end. It will make itself known.

“There is the end in terms of the final scene and then the end in terms of the climax of the film — now that [the latter] is something you will be pushing for all the time, from the very beginning of how you conceive the project, until the last possible shoot and edit, you’re always refining for that point. The final scene that closes out can come at any point. And forget about trying to tell the Truth. Just as there is no original idea, Truth, perhaps more so, exists on a spectrum. – Dick

READ MORE: How to Win an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature (Or at Least Try)

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.