By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Are These the Next Master Filmmakers From Around the World? Lessons From New Directors/New Films

Eric Kohn

Talent is generally noticed when it has company. From the French New Wave to mumblecore, new filmmakers tend to receive widespread attention when they’re lumped into the perception of a movement, whether or not it actually exists. That notion was refreshingly set aside by the set of options included in the recent New Directors/New Films series in New York, which concluded its 42nd edition over the weekend. The program, a joint initiative of the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the Museum of the Modern Art, provided a broad international survey of international cinema that’s anything but consistent. And that’s part of the reason why this was one of its strongest editions in recent memory.

With more movies being made around the world than ever before, it’s harder to pinpoint emerging filmmakers who could one day become great masters. But the spectrum of voices is appropriate. Working with a wide variety of genres, reacting to all kinds of different cultural motives, paying homage to the past or pushing to tell stories in new ways, these younger directors are working in specific ways bound to hold appeal for certain audiences. In an age of customization, audiences demand a range of possibilities; fortunately, few filmmakers are sounding the same notes. Of the 17 features I saw in the 28-film lineup, hardly any shared subject matter or style. But they did echo various sensibilities about filmmaking and society that illustrate some of the nascent qualities sure to define a new generation of creators. Here are a few takeaways about these potential new masters of the medium.

Old Masters Live Again

Thanks to the proliferation of distribution outlets, cinephiles are better suited to explore more facets of film history than ever before, and the outcome shows in several first-time features that are remarkably in tune with the work of master directors. Rather than paying blatant homage, however, these new movies use their references as starting points for original narratives that also function on their own terms. In one example, Tudor Cristian Jurgiu’s “The Japanese Dog” is fully in line with the tender family yarns directed by the late Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu. That’s especially noteworthy since Jurgiu hails from Romania, a country that has been largely associated with dreary real time thrillers like “4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days.”

Jurgiu’s delicate portrait is a refreshing contrast that’s emotionally potent without an iota of overstatement. Its slow-burn plot involved an old man (longtime Romanian actor Victor Rebengiuc) attempting to put his life together after his wife is killed in a flood; when his estranged son arrives with his Japanese wife and young child, the family’s troubled history gradually comes to the foreground. Jurgiu populates his story with patient long takes and quiet exchanges that make the main character’s struggles utterly involving before any of his past grievances come into view. The result is a compelling portrait of poignant drama emerging from the rhythms of real life.

A similar effect is achieved with more experimental processes in “The Strange Little Cat,” Swiss director Ramon Zurcher’s pensive look at the frustrations surrounding domesticity. Set in a suburban household over the course of a single day, the movie stretches far beyond the exploits of its titular feline to showcase a mother at wit’s end contending with her whiney young daughter and various other relatives orbiting the flat as various mundane activities pile up. The movie has a sustained hypnotic quality that elevates seemingly basic actions to a form of cinematic poetry that’s at once insightful and absurd, ably calling to mind the work of Jacques Tati, whose abstract slapstick approach was clearly ahead of its time.

Then there’s “The Strange Color of Your Body’s Tears,” Helene Cattet Bruno Forzani’s numbingly intense consolidation of seemingly every stylistic quality of Italian giallo films stuffed into a single viscerally unnerving package. The filmmakers’ nightmarish portrait of a man struggling through an ominous apartment searching for his missing wife applies neon blues and reds to a confounding tale told in fragmented visuals ranging from countless splits screens, slo-mo and oodles of blood. It’s a terrifyingly uneven experience that successfully resurrects long-defunct techniques and transforms them into an aggressive form of pure cinema.

Workplace Confusion

In the post-recession era of workplace anxieties, filmmakers have turned their cameras on the conundrums facing various characters caught between their personal and professional desires with an unprecedented mixture of anger and insight. Richard Ayoade’s dystopian “The Double” turns a Dostoyevsky novella into one of the finest dark comedies involving office problems since “Brazil,” with Jesse Eisenberg as an alienated young drone whose job security is threatened by the arrival of competition in the form of another man who looks exactly like him. With its dreary, poetic atmosphere and surrealist sense of uncertainty, “The Double” smartly assails the paradoxes of struggling to have value as a cog in the machine. But while Eisenberg’s character mostly struggles to make his feelings count, the lead character of “Buzzard” continually attempts to defy the system, hilariously ripping off the bank that employs him with no regard for the consequences—until they catch up to him with dire results. Joel Potrykus’ twisted satire is like “Office Space” on crack, featuring a wickedly twisted character with the kind of anarchic attitude that could only emerge from today’s troubled job market.

Other figures in the New Directors/New Films lineup suffered from having their identities consumed by their professions. Anja Marquardt’s haunting “She’s Lost Control” focuses on the dilemma facing a New York-based sex surrogate who may or may not be falling in love with one of her clients. The young woman in question, played with a mixture of fragility and assertiveness by Brooke Bloom, maintains a sense of confidence about her professionalism that’s destined to crack—but the movie’s cryptic atmosphere makes it entirely when or how this might happen.

That same fundamental problem unfolds with hilarious results in “Obvious Child,” Gillian Robespierre’s giddy comedy starring standup comedienne Jenny Slate as a woman seemingly trapped in the cadences of her humorous routines to the detriment of her personal life—to the point where her boyfriend dumps her after she works him into her onstage routine. The ensuing comedy has serious bite (including a plot point that involves abortion), but “Obvious Child” glides along with the sustained goofiness of a polished studio-produced comedy…except it’s a lot funnier, and more honest, than any female-centric cinema produced in Hollywood today.

Reckoning With History

Another corrective to a deficiency in the commercial marketplace, Justin Simien’s hilarious satire “Dear White People” focuses on the travails of several black characters at an Ivy League college littered with racial confusion and more than a little actual racism. Simien’s characters speak with rapid-fire exchanges typical of a screwball comedy, but they’re also littered with topical reference points and an overarching sense of yearning for everyone to get along in the throes of a national identity crisis. The genuine statement of the Obama Era, “Dear White People” eloquently captures a society in transition.

Albert Serra’s “Story of My Death” also examines a shift of attitudes and ideas from a very different period. The Catalan director’s nutty period piece begins as a straightforward look at the life of late 18th century rationalist Casanova before abruptly shifting into a portrait of 19th century romanticism with the arrival of Dracula. Serra’s mystifying allegorical narrative has the transfixing quality of thumbing through history books and legend at the same time, suggesting that our perceptions of the world are shaped by an unseemly combination of both. Experimental directors Ben Rivers and Ben Russell take that possibility one step further with “A Spell to Ward Off the Darkness,” a nearly wordless three-part odyssey that explores the experiences of a black metal band member from his time spent on a commune, in solitude, and finally onstage. This ceaselessly cryptic overview of various utopian ideals has a sustained meditative quality that’s alive with the desire for personal satisfaction and confused about whether or not it can ever be achieved.

Truth, Fiction and Everything In Between

Much has been made about the boundaries between fiction and documentary cinema growing more and more porous as filmmakers disregard them in favor of inventing new approaches. To that end, the handful of titles that incorporated documentary elements at this year’s New Directors/New Films series formed a cogent prologue to the Film Society’s upcoming “Art of the Real” series, which magnifies this process even further. Even the sole “traditional” documentary in the New Directors lineup, the Syrian-produced “Return to Homs,” has the aura of a next level accomplishment in documentary form, with its handheld digital camerawork shot in a literal war zone, containing footage that would’ve been virtually impossible to capture more than a decade ago.

The versatility of the documentary form has yielded a greater sensitivity to film form. Italian director Roberto Minervini’s “Stop the Pounding Heart” begins as a plotless look at daily life among a family of Chrisian goat-farmers in rural Texas. But Minervini’s quasi-fictional look at the exploits of the Carlson family slowly develops an emotional core by fixating on the perspective of confused teenager Sara, who plays herself as she grapples with questions of faith and responsibility. Less documentary than document, “Stop the Pounding Heart” provides a snapshot of the coming-of-age experience with a shocking amount of intimacy.

On a more outwardly ambitious scale, Jessica Oreck’s “The Vanquishing of the Witch Baba Yaga” combines storybook imagery and accounts of a Slavic fairy tale with footage of contemporary Romania, Hungary, Poland, Ukraine and Russia to create a fascinating ruminative essay on the role of mythology in shaping national conciousness. The titular story represents primal fears that society as a whole may willfully repress even as it defines its boundaries. “Culture imagines an inherent advantage over the wild and builds high walls to keep it out,” the narrator explains at one point. But “Baba Yaga” is shrewd enough to find a way in.

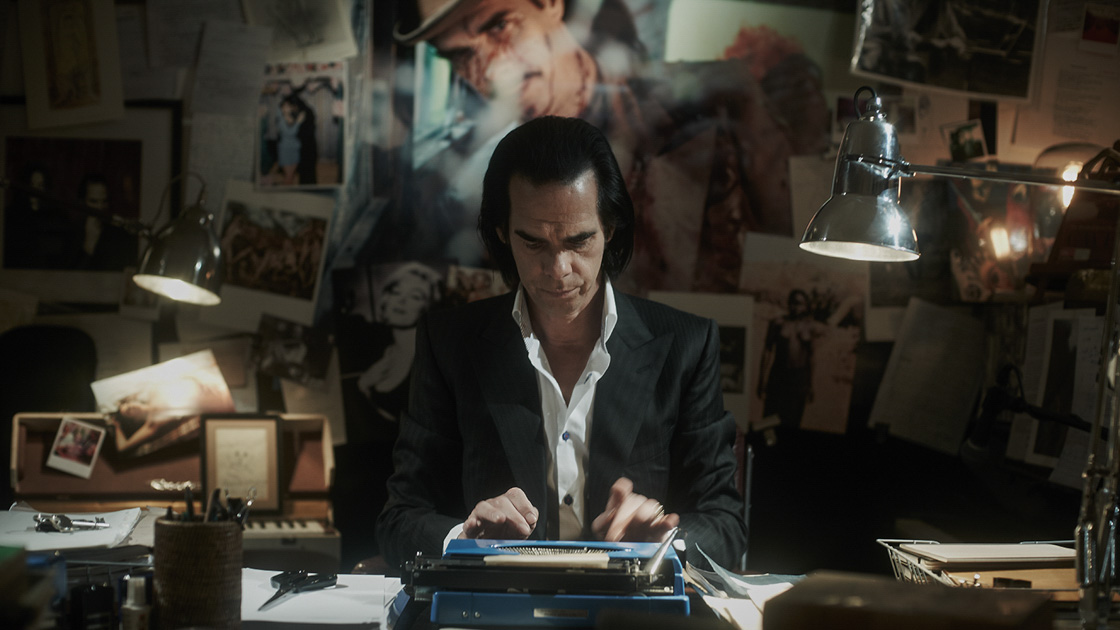

Also burrowing into places no traditional documentary can go: Ian Forsyth and Jane Pollard’s “20,000 Days on Earth,” a clever experimental riff on the life and art of musician Nick Cave that drifts through his creative consciousness more than it surveys the history of his career. The movie contains enough slick footage of his performances to prove that one could easily put together a Nick Cave concert documentary with little originality and it still might offer plenty of snazzy content.

But “20,000 Days on Earth” displays a far greater degree of innovation that makes it one of the most unique artist profiles to come along in ages. Reflecting on his process and the personal experiences that have defined his output, Cave is essentially cast as a character in the drama of his life: conversing with a therapist, talking with friends as he drives around town, sifting through his archives and hanging out in the studio, he’s perpetually caught between self-analysis and artistic frenzies. The movie brilliantly epitomizes a state of awareness that Cave describes as “that place where imagination and reality intersect.” To a largely satisfying degree, that description suited many of the selections from this year’s New Directors/New Films, which had as much to say about the quality of filmmaking around the world at the moment as it did about the promising directions it may soon take.

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.